Women join the sex industry for many different reasons; for some it begins as a choice, for financial gain, self-empowerment or lack of opportunity.

But for many, deception and desperation forced them into an unregulated, dangerous industry.

Acting executive director at Project Respect, Rachel Reilly, believes that whatever the reason, women still find themselves in exploitative conditions both financially and physically.

“It’s one thing that they are led to believe and then it’s another what they are to experience,” she tells upstart.

Project Respect is a support and referral service based in Fitzroy, Melbourne, for women in the sex industry who have been trafficked or exploited.

“We outreach to the 91 licensed brothels across the greater Melbourne region. We are a friendly and supportive service for women if they need help, then we connect them to other organisations,” she says.

Victoria was the first state to legalise brothels under the 1994 Sex Work Act. The current system for sex work in Victoria is licencing, a four piece legislation including the Sex Work Regulations 2016.

The laws for sex work in Australia vary considerably from state-to-state, with brothel work still considered illegal in many parts of the country.

Even with early legalisation in Victoria, illegal trafficking and sex work remains a prominent issue in Melbourne.

“So for the 91 brothels in the greater Melbourne region, it is estimated that there are about 500 illegal brothels offering sexual services,” Reilly says.

These illegal brothels are often disguised as massage parlours, beauty shops and karaoke bars in Melbourne and its outer suburbs.

“In amongst that women are forced to work whether they would fit into the definition of human trafficking, I can’t say, but I can say that there’s exploitation, serious exploitation.”

“It’s in front of our eyes, but it’s sort of like a can of worms. There’s a wide range of regulators and enforcement people that should be working in the illegal brothel space, but everyone sort of says that it’s someone else’s responsibility and through that no one takes ownership.”

In the past two years, Australia has had zero human trafficking convictions. In 2014, the Australian Federal Police investigated 87 alleged cases of trafficking and 46 the year before; none were convicted.

“It’s illegal, the punishment is small given it’s one of the most heinous human rights violations that you can perpetrate on another human being,” Reilly says.

“We’ve got a push around gender equity strategies and family violence, and there’s actual evidence of illegal sex work and trafficking online, but no one will address it as an issue.”

Former Melbourne sex worker, Genevieve Gilbert-Quach, was in the industry for eight years, experiencing daily accounts of rape and violence, labelling it as an occupational hazard in the industry.

“So I came here as a student and I fell into the sex industry,” she tells upstart.

“I came from Montreal, so I came to study a masters of multimedia and then I had a lot of debt. I said to myself that I would stay only 8 months to pay it off the $50,000.”

She entered the industry in the early 2000s, working in Melbourne’s high-end brothels for several years where she learnt much on the power and secrecy in the industry.

“Men with money can call anyone to do anything,” she says.

She was often abused and submissive to wealthy businessmen and drugged by clients without consent, causing post-traumatic stress disorder when she left the industry in 2009.

This prompted Gilbert-Quach to go on and fund the Pink Cross Foundation in Melbourne, an organisation aimed at supporting women in the sex industry and those trying to transition out. Her organisation relies on donations, with little assistance from the govermnent.

“I got into it and couldn’t get out, so my goal is to be a presence,” she says.

She believes that family issues and violence can lead women to enter the industry along with a lack of education.

“It’s always the case for women in the sex industry, it’s always about money, or poverty, family abuse and trauma is a big factor as well,” she says.

“I got trapped and tried to leave and run my own business in web design, but it’s a competitive space to be, just like any field. My English wasn’t good and that’s what keeps a lot of foreign women in the sex trade, our language, we don’t have the same contacts or accent.”

https://twitter.com/PinkCrossOz/status/802144421298868224

In the past year, Reilly has conducted almost 300 visits to Victorian brothels, with the biggest issue remaining the same; significant language barriers.

“65-70 per cent of the women that we meet are from predominantly south-east Asian backgrounds, and they have limited language skills,” she says.

“So if they have limited language skills you can imagine how hard it would be for them to navigate safe sex and set what they are and aren’t going to do.”

Alongside the physical and mental abuse, Reilly also identifies licensing as another form of exploitation.

“The women are not covered under the Fair Work Act, they are treated as independent contractors, they should be able to dictate how much they make, but it’s the brothel owners that dictate how much they can make,” she says.

“You and I are covered under the Fair Work Act, if something goes wrong, we can go and make that complaint, so that’s made even more complex by the stigma and discrimination of being involved in the industry.”

For Gilbert-Quache, the problem lies beyond licensing.

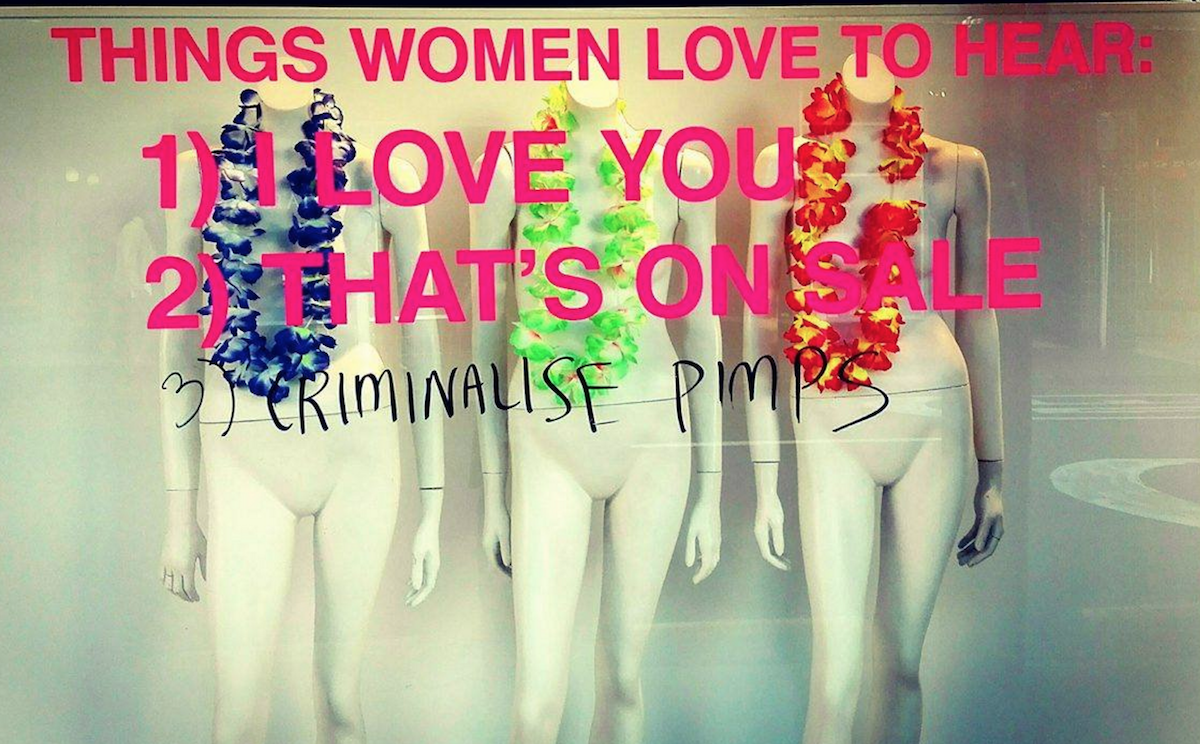

“We believe women should be in other places and not subordinate to men’s sexual needs. If you respect and encourage women, we all need to ask the question of why is this legal?”

Eden Hynninen is a Bachelor of Journalism/International Development student. You can follow her at @eden_hynninen.