When most Australians went to the polls in 2013 voting for their preferred Senate representative was as simple as writing a 1 in a box. However, thanks to reforms slated to pass through federal parliament in coming weeks, the 2016 elections won’t be quite so easy for many voters.

The changes, which will significantly change the way Senators are elected, have been the subject of a heated debate in Canberra over the last two weeks. The Coalition and the Greens are backing the move in the face of criticism from the Labor Party and many independent Senators.

So, what exactly do the reforms mean for voters going to the polls later this year? Who stands to benefit the most? And what might the upper house look like at the start of 2017?

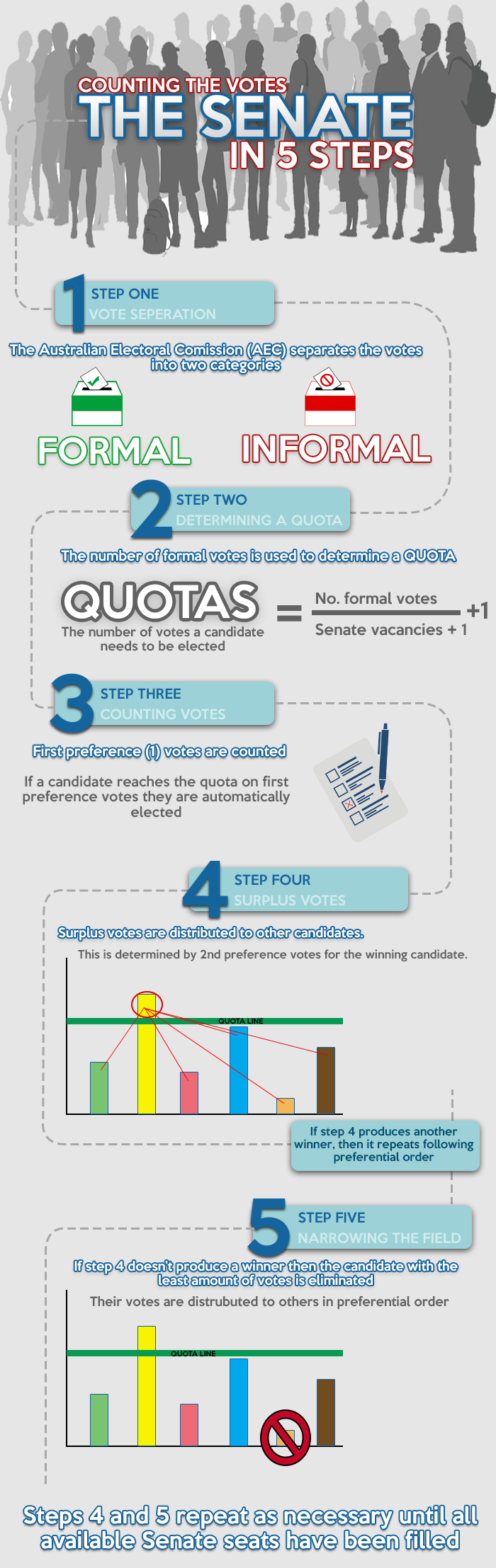

First things first, the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Bill 2016 includes a number of key changes:

- The effective abolition of group voting tickets

- The introduction of “optional preferential voting” above-the-line

- Changing below-the-line voting to an optional preferential system

- A savings provision for above-the-line voting coupled with an increase in the amount of allowable mistakes below-the-line

- Logos on ballot papers to avoid confusion between parties with similar names

What’s all this above and below the line business?

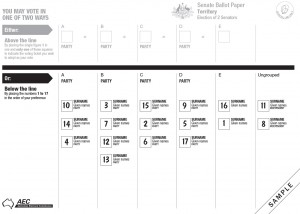

The characterisation of senate voting as either “above” or “below” the line stems from earlier reforms made to the senate ballot paper in 1984, and will still be applicable to the new voting system. The terms reference the thick black line on Senate ballot papers that separates two types of voting.

Below-the-line voting has traditionally been a more time consuming process. It involves a voter assigning a numerical value to candidates based on their preferred representative. For instance, if there were 100 candidates listed below-the-line, a voter would need to rank each one from 1 (most preferred) to 100 (least preferred).

Below-the-line voting has come under scrutiny for the demand it places on voters. During the 2013 election in Victoria, there were 97 candidates listed below, meaning that anyone voting this way would need to fill in close to 100 boxes to make their vote count.

The proposed changes to below-the-line voting will make this process less demanding by asking voters to number as few as six boxes below-the-line in order to submit a formal vote. However, should voters choose to do so, they will still be able to fill in all the available boxes.

By contrast, above-the-line voting was created to make Senate voting much easier and has traditionally involved voters just numbering one box for their most preferred party or group, deferring the duties of preference allocation to those they lodge their first preference for. It’s similar to those how to vote cards that volunteers hand out at polling stations – except that it’s implicit in the vote itself.

This is where the contentious group voting tickets come in. In anticipation of above-the-line votes, parties and groups lodge documents with the Australian Electorial Commission (AEC) outlining what preferences to allocate to their above-the-line votes. This preference ordering is decided in what are often private deals between major and minor parties, and considering that 95% of Australians voted this way in 2013, their impact can be immense.

For instance, as a result of this preference swapping a representative from The Motoring Enthusiast Party, Ricky Muir, was elected into the federal Senate with just .5% of the primary vote. The Coalition has picked up on this, and has used it as supporting evidence for their reform, which would effectively abolish these tickets.

Instead, above-the-line voting would change to an optional-preferential system whereby voters would indicate at least six preferences above-the-line. This would transfer democratic power back into the hands of voters, or at least that’s what supporters of the reform claim.

However, the reforms have also included a savings provision, which will mean that merely numbering one box above the line will still result in a formal vote being casted. This has been included with the hope that there won’t be a spike in informal voting because voters become confused by the change.

Who supports this and why?

The key supporters of this bill in federal parliament have been The Coalition (who introduced the bill) and the Australian Greens. I know right? Weird combo.

Greens leader Senator Richard Di Natale has qualified their support saying that the bill is a “hugely important democratic reform,” but the move may also benefit the Greens strategically.

Professor Dennis Altman, a Professor of Politics at La Trobe University, was supportive of the reform and offered an explanation for why the Greens may support the policy.

“I think that [the Greens] feel it is a way of getting rid of a few of the right wing individuals in the senate and ensuring that they get back to the situation they had in the past of actually having the balance of power. But I think it’s a mix of immediate self-interest and genuine commitment to a more workable system,” he tells upstart.

The Greens’ support for the bill has attracted considerable criticism from the senate crossbench, with Senator David Leyonhjelm characterising the move as a “dirty little deal” between the Coalition, the Greens and Nick Xenophon.

Minor parties stand to lose the most from the reform, given that they typically rely heavily on preference deals rather than primary votes to get Senators elected.

The leader of one such party, Dr James Jannson, who leads the Sydney based Science Party, criticised the reforms. He says that they will likely result in many votes exhausting before the voting has concluded.

“The main issue is that it causes people’s votes to go to waste. The Group Voting Ticket was a way to make sure that your vote would count right until the end of counting, without having to number all the boxes.”

The new system means votes will expire if you don’t number every box above the line, and hence has made voting effectively more difficult,” he tells upstart.

Jansson also says that the reforms could spell disaster for parties that are perceived to be similar to one another.

“It will cause the vote to split between parties with similar demographics (because not all votes will transfer). The same effect will be seen with the Greens and the Labor Party,” he says.

“I don’t know anyone who thinks that Australian democracy would be better if one of those two parties were no longer a choice.”

Whether the changes are good for democracy or not, they are expected to pass Parliament in the coming weeks, which will mean that the next time Australians take to the polls they will road test the new system themselves.

As for the state of the Senate come 2017? Well, that depends largely on whether the Coalition call a double-dissolution election, which would likely see most independent senators out of office by the end of the year.

Matthew Elmas is a final year journalism major at La Trobe University. You can follow him on twitter: @mjelmas