At any given time in Australia there are around 1,500 people on waiting lists to receive organs or tissue.

In 2014, the lives of 1,117 people were saved or drastically improved in Australia thanks to successful organ donations from 378 people, or 0.00161 per cent of the population.

The number of organ donors and transplant recipients in 2014 was the second-highest since national records began in 1989. But why did only 0.00161 per cent of the Australian population donate if 76 per cent say they would willingly donate their organs?

A major factor could be that Australia uses an opt-in organ donation system, meaning that registering is voluntary.

Currently, people register and choose which organs they would like to donate. Advanced medical technology means that major organs such as the heart, kidneys, lungs and liver are transplantable, as well as heart valves, bone, skin and eye tissue.

Unfortunately, many Australians are time poor. Some are too busy to contemplate or discuss life after death, whilst others may feel uncomfortable about the topic.

Changing to an opt-out organ donation system would mean that those willing to donate their organs wouldn’t have to take the time to register. Every person would be an organ donor unless they chose to indicate otherwise.

Still, even when someone is registered to become an organ donor, there is no guarantee that they will go on to make donations.

Less than one per cent of people die in a way that makes the donation of their organs and tissue possible. Transplants are only performed when all other forms of medical treatment have failed to save the donor and particular organs are still salvageable.

Additionally, a study published by the Medical Journal of Australia found that rates of next-of-kin consent have been low, resulting in even fewer donors.

Australia is a world leader when it comes to successful transplants, but with such a small number of donors, and an even smaller number of people who die in a way that makes organ donation possible, our success rates are very low.

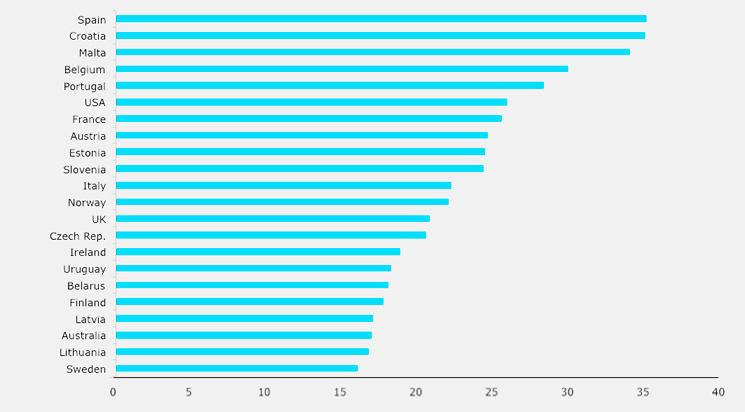

The International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation (IRODaT) ranked Australia 20th in a worldwide study of successful transplants. Spain, on the other hand, is the world leader for organ donation, and operates an opt-out donation system.

In an effort to increase the number of organ donors, the Australian government, with state and territory governments, implemented ‘A World’s Best Practice Approach to Organ and Tissue Donation for Transplantation’. This program aims to increase clinical capacity and encourage community engagement and awareness.

Zaidee Turner passed away in 2004 at the age of seven from a cerebral aneurism, which is a burst blood vessel in the brain. She was one of the youngest Australians to donate her organs that year, and her gifts saved and improved the lives of seven people.

Zaidee’s parents, Kim and Allan Turner, founded Zaidee’s Rainbow Foundation not long after her death.

Allan told upstart that he and his wife promote the campaign through products such as Zaidee’s Rainbow Shoelaces. Sporting associations have supported the campaign including AFL, netball, cricket, basketball and soccer teams.

Allan said that his family signed up to the Australian Organ Donor Register in 2000, just four years before Zaidee passed away.

“Zaidee was three at the time and of course she didn’t understand,” he says.

“When she was six-and-a-half, she turned around one day to Kim and said: ‘Mummy, if anything happens to me, I want to donate my organs and tissue to other kids’.

“We thought that it was an unusual thing for a child to say, but seven months later she passed away and we carried out her wishes to be an organ and tissue donor.”

Allan, who has been working full time as CEO for Zaidee’s Foundation since 2006, believes that an opt-out system will eventually happen in Australia.

“The system would mean that every Australian is forced to discuss their decisions,” he says.

“We are still another ten or so years away from anything happening because we still need a lot of education in the community about what organ and tissue donation is all about.”

Allan said that without this education, an opt-out system could turn people against organ donation.

“If the government introduced this new system and told everyone that they’d be an organ donor when they died, I think a lot of people would take that as a threat and sign off the registry,” he says.

He notes that Spain’s success with organ donation can be attributed to multiple things, not just its opt-out system.

“Their hospital system copes a lot better with emergencies and people in intensive care than ours does here in Australia. Our hospital system needs a lot of improvement before we can get close to capturing the figures that Spain and other countries do.”

The main message that Allan wants everyone to take from Zaidee’s story is to think about and discuss the hypothetical.

“At the end of the day, your family are the ones that can either stop or allow organ donation from happening, so you need to discuss your wishes with them.

“If a seven-year-old girl can be an organ donor, anyone can.”

Visit the Australian Organ Donor Register’s website if you would like to record your decision about organ and tissue donation, and make sure you discuss your wishes with your family.

Joely Mitchell is in her final year of a Bachelor of Journalism degree at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter: @joelymitchell.