Jammi Burgess has been under guardianship of the state for most of her life.

Placed into foster care by her mother at just five-years-old, she has been through almost every out-of-home care program offered by the Department of Human Services.

Out-of-home care encompasses three different programs.

Kinship care is where the caregiver is a family member, foster care is where a child is placed under protection of an accredited carer, and residential care is similar to share housing, only with 24 hour adult supervision.

Burgess tells upstart that these programs offered little support and guidance.

She says she was considered a very difficult child, and experienced numerous placements with foster care families. However, she never stayed with a foster family for longer than two years, and eventually found herself in residential care.

“When you get put into residential care. it’s kind of like you’re just dumped there. You don’t have the support of a foster carer,” Burgess says.

With workers swapping shifts constantly, she found it difficult to form any close relationships.

Burgess says that this lack of support usually means a lot of kids in residential care turn into runaways and drug addicts. For many, this lifestyle continues after leaving state care.

“It doesn’t change because they still don’t have that support,” she says.

Once she turned 18, the system no longer catered for Burgess. She had few places to turn to, and found herself struggling to find stable housing and employment, so ended up living in youth refuges for over a year.

Living rough was difficult for Burgess. She says she occasionally bunked with friends, but was always concerned about where she’d sleep the next night.

[Jammi and her brother, Joshua]

Burgess, now 19, found help through Anglicare Victoria’s Breaking the Barriers program, a support service that works to prepare young people for independent living.

Now living with her brother, she plans to study and earn a degree in social work.

“I was one of the lucky few who ended up in the program,” she says.

“If it wasn’t for my leaving care support, I don’t think I’d be here.”

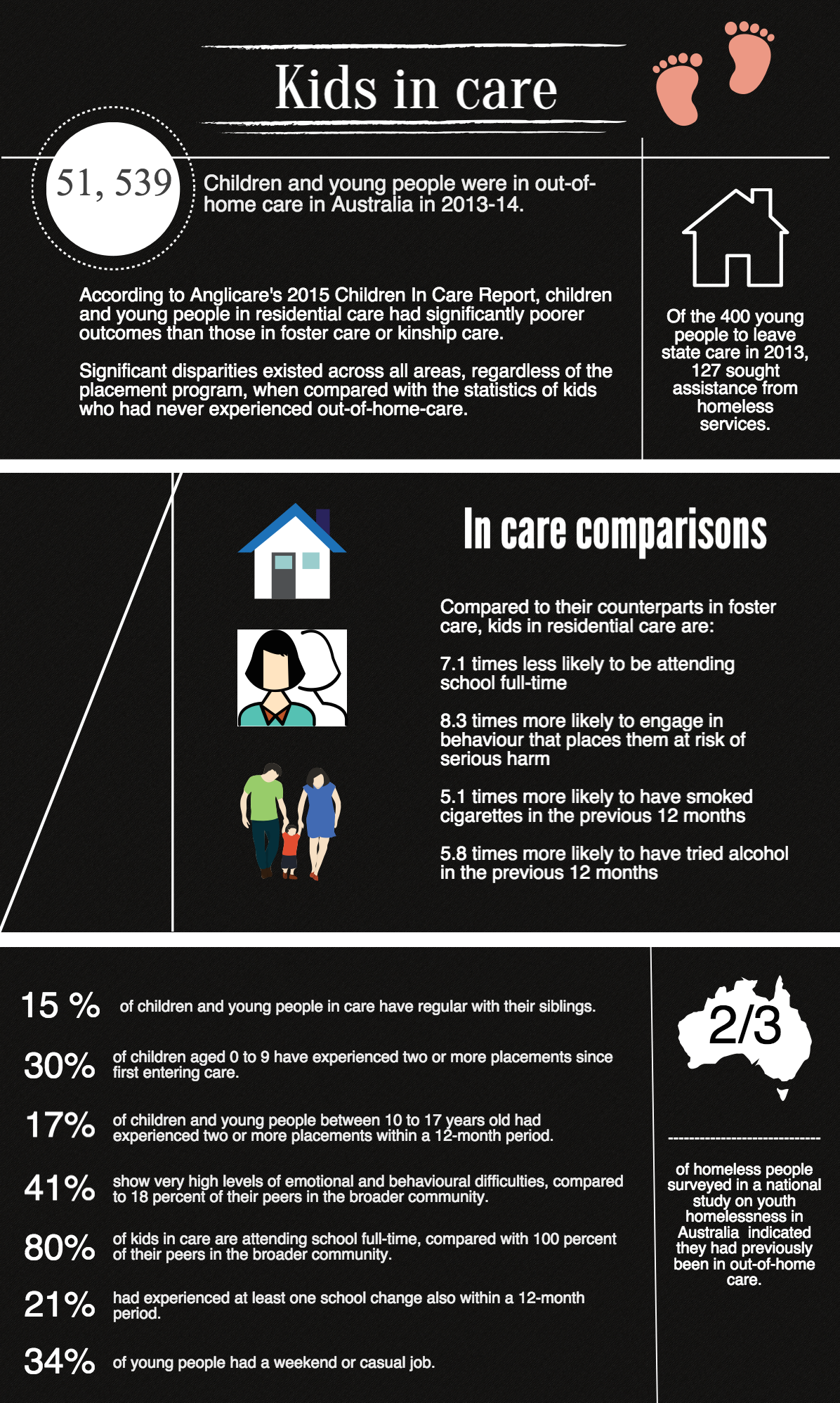

A national study of youth homelessness in Australia identified out-of-home care as a risk factor for homelessness.

The study concluded that being placed in out-of-home care will eventually lead to homelessness in most cases.

There have also been calls to extend the age for out-of-home care to 21. This reflects trends in the wider community, where it’s common for young adults to remain living at home until their early twenties.

Research in the UK and the U.S. have shown young people who remain in care for longer, have better outcomes in their twenties.

This can lead to greater educational attainment and employment prospects, a decrease in unwanted pregnancies, and less contact with the criminal justice system, including incarceration.

Principal researcher at Anglicare Victoria, Tatiana Corrales, tells upstart that the state is failing to meet the needs of the youth under its care.

“There’s a burden of responsibility as the carer of these young people to ensure that when they do age out of the system they don’t just go into homelessness,” she says.

The 2015 Children in Care Report Card, which Corrales is author of, shows blatant disparities between children in state care and those in the wider community.

It also notes that those placed in foster care or kinship care performed markedly better than those living in residential care.

Earlier this year, Victoria’s child safety commissioner, Bernie Geary, released a report that called for the program to be scrapped.

“By the time these kids end up in residential care, they’re older, they have a much higher range of complex needs and have usually experienced a lot of placement breakdowns,” Corrales says.

She believes there should be a conducive way to deal with trauma in the program.

“We’ve got some of the most complex and hurt young people living together and we’ve got a workforce that is perhaps not the best qualified to work with such a high-risk and high-need population,” she says.

As a result, kids who are too old to be in the system are often unprepared to deal with the realities of independence.

The government acknowledges these issues, but is restricted by lack of funding.

“There has been a lot of effort directed towards early prevention and in this respect the government has been very active,” Corrales says.

“We sometimes tend to focus more on the young kids coming into care which makes sense, but to the detriment of the older kids.”

Those aged between 15 and 18 are perceived as the most difficult to work with, but are typically the ones in need of the most support.

“We need to do better than saying ‘happy birthday, you’re 18, and now you’re out’.”

Caitlin McArthur is a third-year journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter: @CaitlinMcArthu1.

Caitlin McArthur is a third-year journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter: @CaitlinMcArthu1.