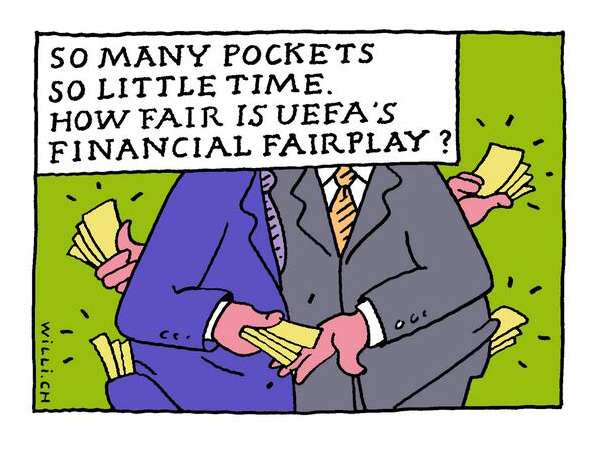

UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) Regulations come into full-effect this season. Above all else, UEFA is trying to make clubs more financially sustainable.

But while this may well occur, these new precedents will also yield an unwanted set of consequences.

At the heart of the Fair Play doctrine is a break-even requirement, which stipulates that a football club’s spending cannot exceed its revenue.

In an environment where nearly all sides borrow in order to compete, the rules’ primary purpose is to prevent financial debt from reaching unmanageable levels.

Teams must instead revert back to basics and focus solely on maximising their relevant revenues through television rights, gate receipts and sponsorship.

This way they will have more to spend, rather than simply just exacerbating their deficits.

The overarching hope is that if teams operate within their means, over-inflated player transfers and wages will be reduced and the discrepancy between rich and poor will be bridged.

But, in a system where the highest revenue-generating teams reign supreme, the established juggernauts will only become more powerful.

The break-even rule does not propose a specific digit figure in which to cap spending, nor limit debt. A club’s success is ultimately contingent on its earning potential.

Financial fair-play rules pic.twitter.com/uFr5IDlgtn

— InsideWorldFootball (@insidewldftball) May 22, 2013

So, under this framework, the likes of Manchester United, Bayern Munich and Real Madrid will always make a greater profit because of their global profiles.

Giants like these have accumulated their assets and popularity over a period of time. As a result, they are more profitable and demand a bigger piece of the financial pie than their poorer adversaries.

But, the reality for the bulk of other clubs, that are historically less wealthy, is significantly different.

Lowlier clubs either rely on subsidies from their owners, or borrow to stay competitive.

Even Nouveau Riche clubs, like Manchester City and Chelsea, will struggle to stay relevant under the new system, because their owners will no longer be allowed to inject funds into their clubs.

Despite recent success helping to build the fan-bases and marketability of benefactor clubs, they simply do not have the same scope of support as the historically affluent. And, consequently, they do not possess the facilities to match their income.

Economics lecturer Dr Liam Lenten appears to concur with this point, citing a club’s support network as a pivotal source of income.

“The club’s ability to compete is its underlying fan-base. And Chelsea might have been considered an also-ran in comparison 15-years ago, 10-years ago maybe, before Roman Abramovich came along. But, even though it’s garnered a lot of new support it [Chelsea] didn’t have before that point in time, structurally, it still doesn’t have a supporter base the size of Real Madrid or Manchester United,” he says.

Manchester United remains a case in point. It has the clout to attract one of the most lucrative shirt sponsorships in the world, through Nike, and one of the more prosperous TV deals via SKY.

Furthermore, it commands some of the highest ticket-prices in England, and Old Trafford, the club’s ground, has a maximum attendance of 75,731 spectators, which is regularly filled to capacity.

To compete with clubs of this magnitude, opposing teams will inevitably need to find shrewder ways to boost their profits.

In this bullish pursuit for the bottom-line, fans are likely to be another casualty in what appears to be an ill-thought-out set of guidelines from UEFA.

With ticket prices and TV subscriptions already at a premium, forcing clubs to exploit their revenue streams for every last penny means that these expenses are only going to become more lavish.

Soon, attending a game which used to be common privilege, could become unaffordable for the common fan. Even watching a telecast of a match may end up too dear.

All this begs the question: is the implementation of Financial Fair Play really worth it?

Granted, it will rid the game of the exorbitant transfer fees and player wages, that have seen it lose its sanity in recent years, but the FFP appears to be a measure that will be more detrimental than beneficial for the beautiful game.

UEFA may have a vested interest in football’s well being, but FFP measures are not the answer to European football’s urgent economic problems.

James Gray-Foster is a third-year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow him on Twitter: @JamesGrayFoster

James Gray-Foster is a third-year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow him on Twitter: @JamesGrayFoster

(Photo: Twitter – @insidewldftball)