One of the biggest sectors within the multi-billion dollar gaming market is free-to-play games.

Among the most successful of these games is Valve’s Dota 2, which earns nearly 20 million a month, while its main competitor League of Legends earns that every day.

This style of game (Free to Play, or F2P for short) has capitalised on the player’s vanity and laziness as a means to monetise an otherwise free game. F2P games appeal to their players vanity by selling them different outfits or hats for their players (which typically sell very well), and appeal to their laziness by selling ways to speed up progression through the game. Neither of these additions are essential to playing the game though, nor do they actually benefit the player in a match, which is the reason the idea is working so well.

As part of their design, Free-to-Play games are designed to be long-term games. Where the Call of Duty franchise releases a new game every year, free-to-play games like Dota 2 last for years without a sequel, with updates and expansions used to sustain activity. They tend to make more money than standard games, but over a longer time frame.

With this in mind, free-to-play games need to be more considerate of their players and take steps to avoid alienating them. A single user may put in hundreds of dollars over the course of the game, but paying users also need other people to play with. Non-paying users are just as important for the longevity of the game, and their profits, as paying users are.

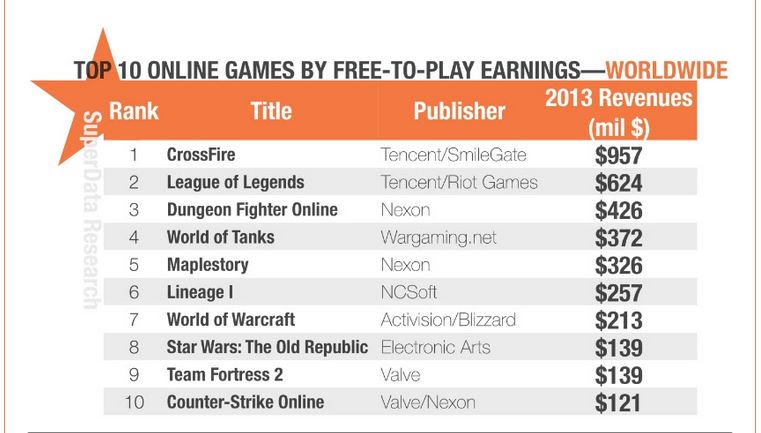

The most recent statistics on free-to-play games’ earnings. Note that all except World of Warcraft don’t require anything to start playing.

The most recent statistics on free-to-play games’ earnings. Note that all except World of Warcraft don’t require anything to start playing.

Expecting people to put in money for a game when there’s no practical gain from it seems strange. But traditionally gamers have scorned games that offer advantages for money instead of skill or effort, preferring systems that are more ‘fair’.

These ‘Pay-to-Win’ games don’t sit well with their target audience, and end up driving away much of their communities. Payday 2 is attempting to introduce a small amount of pay-to-win mechanics into the game for example, and the resulting outrage has seen the games user rating drop a full 10% in a week and server numbers plummet.

But the vanity/laziness sort of models work the best for keeping both types of players involved and the game populated for a longer period of time. Most of the successful free-to-play games avoid the ‘Pay-to-Win’ model and stick with ones that don’t make paying players any better than non-paying players.

New Zealand made Path of Exile has used cosmetics as their only selling point in the game, refusing to sell anything that offers an in-game advantage. Path of Exile has over 7 million accounts registered with the game, and has just released its third major expansion for free. The game is completely playable for free, from start to finish.

“Some people love cosmetics. They love to show off,” Path of Exile’s lead programmer Jonathan Rogers told Polygon.

“There comes a point when you play a game a lot that it ceases to be a game and it becomes a hobby, and laying down extra money for a hobby is not so strange. It changes the relationship with the game, makes it more personal.”

Though Rogers that they “probably would make more money if they went pay-to-win”, Grinding Gear Games still made enough to cover costs and keep expanding the game without alienating the players. Only about 2.2% of users in free-to-play games make up nearly half the revenue, so retaining both paying and non-paying players is essential for the game to remain profitable.

The paying players provide income, but the non-paying players help provide critical mass for the game itself. Considering that most free-to-play games are Massively Multiplayer, with thousands of players playing on the same servers as the same time, player retention is crucial for a free-to-play game.

The alternative strategy is to create a system where money saves time and effort, but doesn’t give you an advantage over non-paying users. With enough time and effort, anything in one of these free games can be unlocked.

League of Legends uses this as part of their scheme for the game. You can purchase new skins for your characters, just like in Dota 2 or Path of Exile, but you can also purchase entirely new characters with money. But at the same time, the new characters can be earned for free without paying anything. You can grind for them, or pay for them, there’s no difference.

This sort of system generally more successful since it gives players an incentive to buy something than cosmetics, while at the same time players who don’t pay aren’t disadvantaged either. Cosmetic-only games still make profits, but of the top four free-to-play games two (League of Legends and World of Tanks) use some form of a time-saving system to get money from their audiences. One uses cosmetics as the main selling point (Dungeon Fighter Online), and Crossfire is a pay-to-win Asian title that hasn’t had much success with Western markets.

Wargaming, makers of the massively successful World of Tanks, call the idea ‘Free-to-Win’. Almost everything that can be purchased in-game, from better ammo to a better trained crew, can be paid for with earned credits or bought gold. The only problem is that this takes time, which is where a lot of users decide to pay.

Hugely successful World of Tanks has managed to have 1.1 million users online at the same time, and claims to have over a 100 million registered users.

Jasper Nicholas, Wargaming’s manager for the Asia-Pacific region, explains that “If you’re the kind of person who can’t spend three hours to gain a certain number of experience points and you want to cut it in half, then you can pay for it. It doesn’t really give you any other advantage.” The World of Tanks micro-transaction model works so well that it averages more revenue per user than any other free to play title.

The downside to this sort of model is that it often walks a fine line. Everything in a game may be free, but in some games putting in money ends up being needed to progress. War Thunder for example, has progression in the game so slow that you either need months of free time, or weeks with a paid account, to get anywhere. The time-saving model works, but it’s hard to perfect.

That’s the entire free-to-play industry in a nutshell though. The ideas work, as evidenced by the big hitters like League of Legends and Dota 2, but perfecting those same ideas for completely different games is difficult. But the base idea, of making profits off games that are free to play, has proven itself and then some.

Michael Martino is a third-year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow him on Twitter: @Darth_Martinus