This year, thousands of high school students will knuckle down and prepare to sit a series of nerve-racking exams in their quest towards tertiary education.

However, the very system that will gauge their academic performance is being questioned and, if the recent Fairfax Media investigation is anything to go by, the four-digit number is fast losing relevance.

The investigation reveals that some universities are accepting students with an ATAR as low as 30.

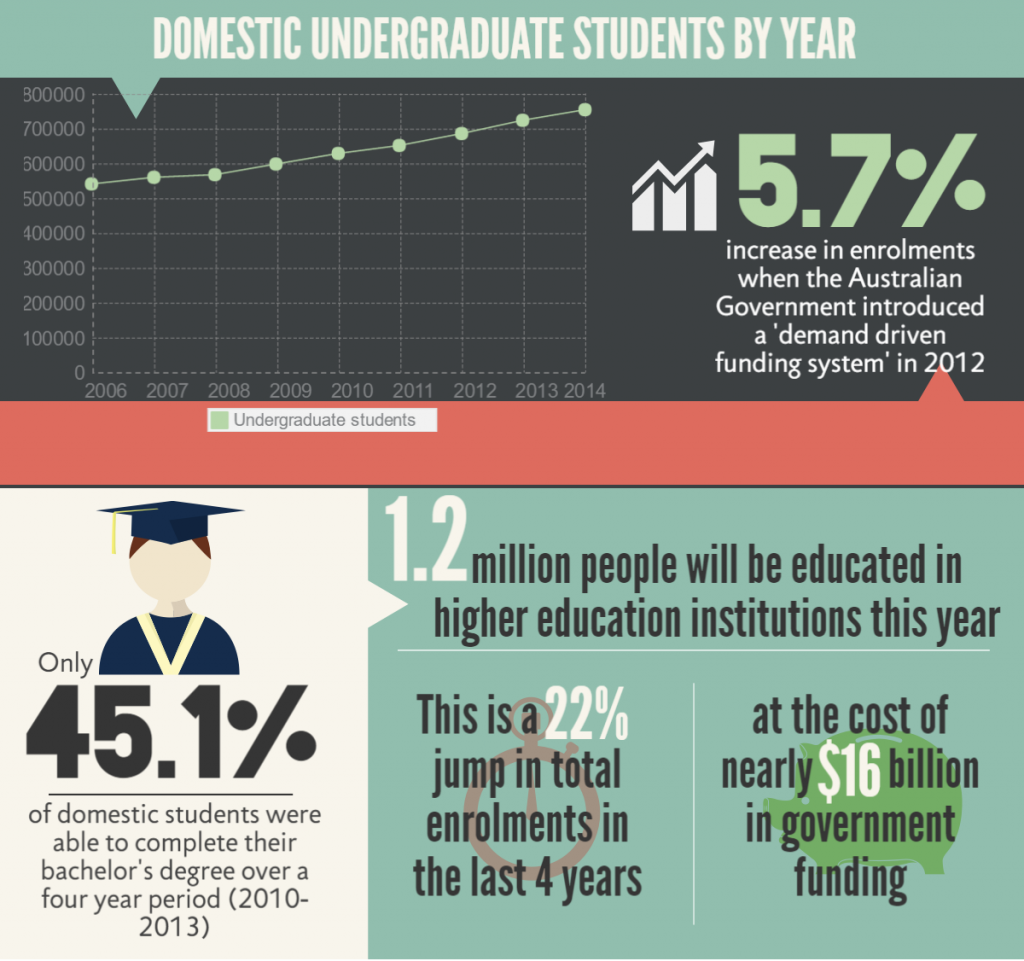

The Gillard government’s decision in 2012 to remove capped funding and enrolment targets for bachelor degrees painted a vision for 2025 where students from all walks of life would have access to tertiary education.

This has meant that Australia’s education model has gradually shifted from an elite system of higher education to a mass system.

In an attempt to allow students from all backgrounds and socio-economic statuses into tertiary education, universities are growing substantially in student numbers – quite often admitting students with significantly lower ATARs than their initially advertised scores.

At the University of Western Sydney, an astounding 74 per cent of students were accepted into a Bachelor of Medical Science degree despite not meeting the cut-off ATAR of 75.55. Instead, the average ATAR of the students admitted into the degree stood at 64.9.

According to Victorian Tertiary Admission Centre figures, 45 per cent of students admitted into a business degree at Swinburne University did not meet the clearly-in score of 60.

For a degree in law, 60 per cent of students scored below the advertised ATAR.

The practice of admitting students with much lower ATARs has become the norm, as the university sector experiences a dramatic surge in student numbers.

Researcher in Higher Education at Curtin University, Tim Pitman, says the Gillard government’s removal of capped undergraduate places has had a definite and demonstrable effect on the university sector.

“Although places weren’t officially uncapped until 2012, Gillard signalled her intention to the sector well in advance, meaning that from as early as 2010 universities started making plans to increase their intake,” he tells upstart.

Data from the Department of Education and Training shows a fast increase in undergraduate domestic student enrolments from 2010 onwards.

Offer rates for students with an ATAR of 50.00 or less recorded the largest increase, from 12.0% (13,757) in 2009 to 38.04% (18,353) in 2015.

However, enrolling students with lower ATARs could be problematic as a significant proportion of students with a lower score end up not completing their degree. Only 45.1 per cent of all domestic students in the 2010 cohort were able to complete their bachelor’s degree over a four-year period.

As clearly-in ATAR scores become less relevant, the higher education sector is increasingly looking towards alternative entry schemes to secure students.

Templestowe College is adapting to this change, introducing an option for students to apply for a range of courses at Swinburne University without an ATAR.

This will include students working on a long-term, final year project, where they will demonstrate their skills in a certain area and write a thesis explaining their reasons for their chosen course.

Templestowe College principal, Peter Hutton, says this will be beneficial for students who have talent and commitment “but to whom the ATAR system is not suited.”

According to Pitman, the use of any single metric to calculate a student’s capability is flawed.

“Universities have a wide range of diagnostic tools to assess a prospective student’s potential to succeed and they need to use them all,” he says.

As a range of other criterions such as interviews and portfolio work increasingly become favoured in measuring student performance, VTAC data shows that only one in four Victorian university courses publicised a clearly-in ATAR for 2016.

The competitive and success driven nature of the ATAR system is also being questioned, with high degrees of stress and depression prominent among students.

According to Mission Australia’s annual youth survey, 59.7 per cent of young people aged between 15 and 19 said school and study problems were a major concern, ahead of issues such as body image (51%), alcohol (14.6%), drugs (14.5%), and gambling (7.2%).

After freshly facing the rigorous demands of the ATAR, first year university students have a range of views about the system introduced in 2009.

Vanessa Di Grazia – ATAR: 98.65

RMIT University, Bachelor of Arts (International studies)

The ATAR system didn’t place much pressure on me because I’m super competitive in nature and VCE is basically set up as a competition. Therefore, I think I work well in that framework and during the year I felt quite productive.

However, I do also share the opinion that the ATAR system may not bode well for some highly intelligent people that are just unable to cope with such rigid testing.

So it’s not really fair, and in some instances, interviews and portfolios are often better schemes for entry into particular courses. Overall though, I wanted a really high ATAR and I actually enjoyed studying for it because it felt like an achievement in the end.

Laila Santos – ATAR: 76.20

Monash University, Bachelor of Pharmaceutical Science

The ATAR system brought a range of stress and happiness to me. I chose a lot of theory subjects and at times the amount of work seemed over-whelming.

However, there is definitely a feeling of happiness when you see that all that hard work has payed off in the end. My ATAR is reflective of how much I’d learnt and what I could achieve although it isn’t the best possible method in my opinion.

Especially the use of scaling in study scores is really harsh and I know of students who completed an International Baccalaureate and found it better due to no scaling.

In terms of universities introducing alternative schemes, I think this is a fantastic idea. Today’s world isn’t heavily reliant on book learning as it used to be and in the ATAR system we’re all just numbers, so individuality doesn’t really flourish.

The jobs for our generation are also different and require more than just what you can remember from a textbook, so the consideration of interviews, portfolios and industry experience is great.

The ATAR was introduced as an intuitive and clear ranking of success and academic performance, but the question remains whether there can be a more contextual and comprehensive measure of a student’s achievements.

Deniz Uzgun is a third-year Bachelor of Arts student at La Trobe University and a staff writer for upstart. Twitter: @uzgundeniz.