“I’m going to tell you this, but I don’t want you to tell anyone. I’ve been pulling my [fully grown] sheep out of the fence over the last few months and their throats are ripped out. Something has tried to drag them into the forest but couldn’t get them through the wires, so they’re stuck in the fence.”

This is what our neighbour told my Dad back in the mid-2000s when we were living in the Grampians, right next to the Black Range.

Our neighbour, who didn’t want anyone else to know out of fear of being laughed at, admitted this after Dad had just told him what he had seen when driving my brothers and I to the bus stop a few weeks earlier: a large, black feline-like figure with an abnormally long tail that slinked across the road as we were driving towards it. We never saw it again, and it left no trace of paw prints on the rough gravel road.

“It was much like a puma, that’s the first thing I thought when I saw it,” my father, Graeme Tresidder, recalls for upstart. “It wasn’t a dog it wasn’t a – well if it was a feral cat it was a sort of mutant feral cat. It wasn’t a normal cat.”

From the early 1800s until the present day, there has been reports of these elusive creatures all across the Australian bush. They are most commonly referred to as panthers, a blanket term used to reference the dark/melanistic colour tone of leopards, jaguars and pumas.

The most common theory about their arrival involves American military serviceman during World War Two, who supposedly brought pumas to Australia as their mascots. Dennis, who was interviewed on Ben Beed’s podcast Missing Panther, said his father was an American soldier during this time who was based in Horsham and Ballarat. His father told him about the pumas his camp used as mascots.

“They were only cubs when he saw them released,” he said on the podcast. “They weren’t full grown, only babies. He told me that at the end of the war they couldn’t take them back home, apparently, so they just let them go. They fed them for a couple of days and they just didn’t come back for a third day.”

But this doesn’t explain sightings of the cats pre-WWII. Other theories include circus and zoo escapees, and the widespread exotic animal trade of big cat cubs in the 19th century before it was regulated.

The legend of the panther has been so prominent in Australian folklore, that in the late-1970s, Deakin University launched a study in Victoria. It concluded that there “is sufficient evidence from a number of intersecting sources to affirm beyond reasonable doubt the presence of a big-cat population in Western Victoria.” However, in an addendum to the report, the animal dropping (scat) that was their clearest proof was later re-evaluated to be a regurgitated pellet from a Wedge-tailed Eagle.

Amber Noseda, a wildlife photographer in the Apollo Bay area, appeared in the media last year for photographing a black feline after spotting it in her rear-view mirror, reigniting the discussion about panthers. Despite never saying she thought it was one, she says she copped a huge amount of flak from sceptics who were trolling her, and had to turn off her social media accounts temporarily. She says she would be hesitant to tell people if she ever saw anything like it again.

“I never said it was a panther. All I said was I can see how people think that there’s panthers out there because these feral cats are huge,” she tells upstart. “I’ve got a couple of cats. I know how big they are, and this was a lot bigger than that.”

Professional scalers said the cat in Noseda’s photo was about the size of a 60 litre cooler box. Millions of feral cats roam the Australian bush, and can grow to twice the size of house cats once they have been in the wilderness for two generations.

After appearing in the media, Noseda says reputable people in her area approached her with their own anecdotes, from even as long as 30 years ago. One group said the animal they saw was as long as the bonnet of their car.

With so many sightings, some people have become fascinated with getting to the bottom of the urban legend. Sarah Alsop, who created the Facebook page Strange Creatures of Victoria, is constantly exploring the Otways. She says she has had multiple encounters with big cats – black and tanned in colour – and is confident they are out there. She has set up cameras to try and capture concrete evidence that big cats exist in Australia. Meanwhile, like-minded people post their own videos and photos of potential sightings on her page.

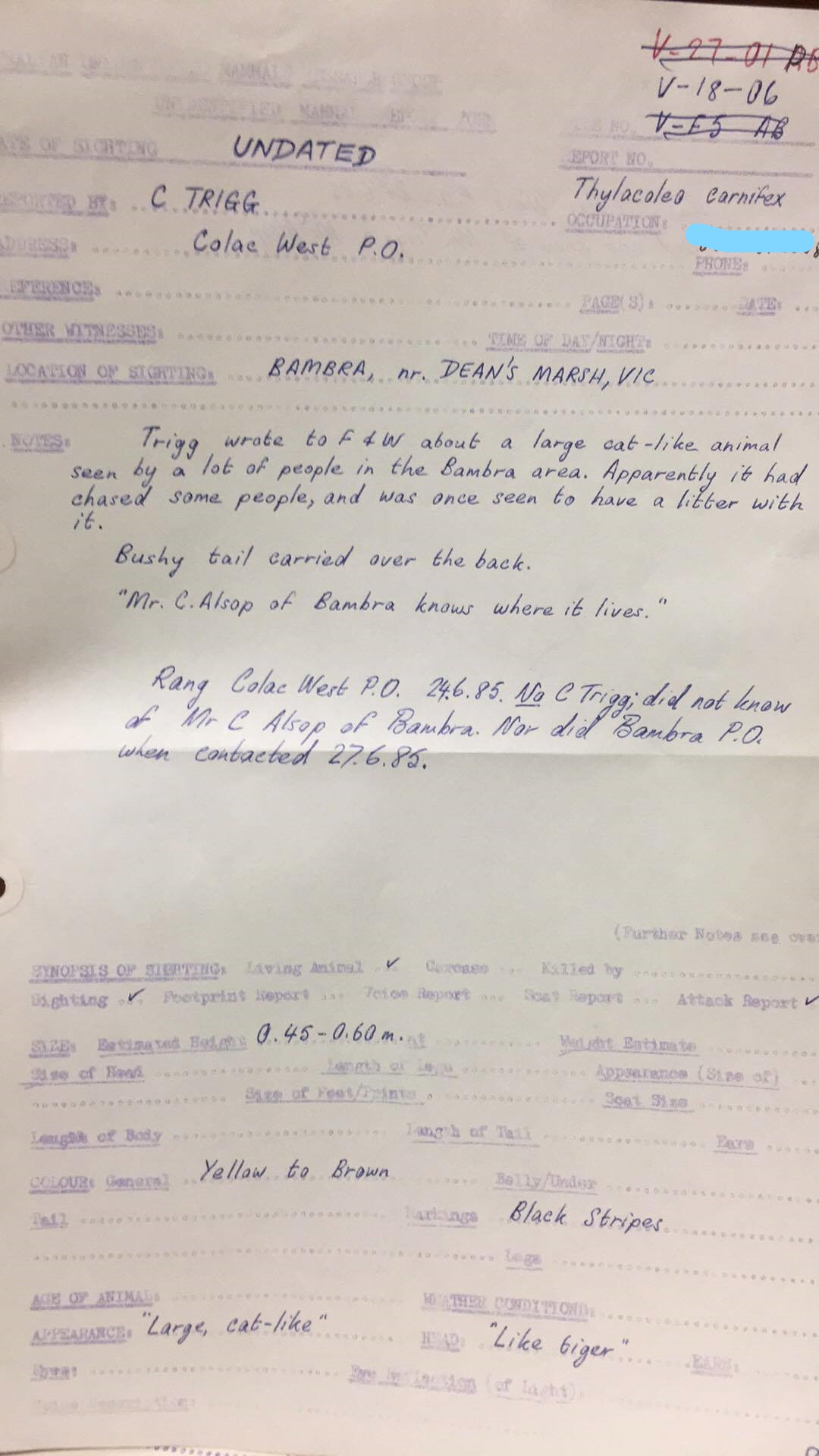

Alsop and others have even claimed that some of the sightings could possibly be a subspecies of the ancient, carnivorous Thylacoleo, or marsupial lion, said to have become extinct approximately 46,000 years ago.

She recalls being contacted recently about a Thylacoleo report from the 1960s that was in the Field and Wildlife (a precursor to Victoria Government Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning) archives, involving her grandpa and another male relative.

The report included details of her grandpa shooting an animal that was described to look just like one to protect his children (Alsop’s mother) as they walked through the bush to school. It said that the two men were both required to lift the animal when they took it inside and placed it on their coffee table (which it fully covered). The report didn’t have any information on what happened to the animal after – if they let it go, burnt it, buried it, etc.

Of course, like every one of these eyewitness sightings and reports it’s hard to know how accurate they are or what the animal actually was. But being such a large country with a large portion uninhabited by humans, Jo Harding, the manager of Australia’s largest nature discovery program, Bush Blitz, says there is still a lot to discover.

“There’s estimated to be about 75 per cent of Australia’s biodiversity that’s largely unknown,” she told the ABC’s RN Breakfast in 2014. “So there’s certainly a lot out there still to find. We’ve discovered 700 new species so far, that’s over the last approximately four years, and we’re still counting.”

As recently as 2016, an ancient dog species that hadn’t had a confirmed sighting for more than 40 years was rediscovered in the extremely remote mountains of Papua New Guinea and Indonesia’s Papua provinces. So it can happen, but no specimen of any unknown, large mammal species has been found during substantial wildlife surveys and research in Victoria in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Some of the most confusing second tier evidence of big cats comes from the unidentified livestock maulings that farmers have reported that don’t match the killing patterns of wild dogs. According to Sarah Alsop, it’s hard to pinpoint what animal in the Australian bush is capable of these kills.

“Going out to where people have lost stock, some of them could be pigs or dogs, but you have to determine the difference,” she says.

According to Alsop, the sheer size of the stock, such as calves and sheep, would be too much for a fox or wild pig to bring down, along with the volume of flesh that is taken away in such a short time frame. Her answer to the lack of primary evidence is that as predators, big cats can be very stealthy.

“The bush is a big place, and if something doesn’t want to be seen or found, it’s going to know we’re there long before we know it’s there,” she says.

Dr David Waldron, a historian who co-wrote the book Snarls from the Tea-tree: Big Cat Folklore, agrees that the most compelling evidence is the stock kills, but remains sceptical until something concrete is found.

“There’s nothing inherently absurd about the idea. But the problem is, if they’re out there, you would be finding things other than second-tier evidence,” he tells upstart. “When you look at melanistic leopards, even places where they are near-extinct, they still come up on trail cameras, they still find scats, they still find carcases after bush fires and that kind of thing.”

He thinks what most likely is occurring is a “gestalt”, where a lot of different things are being shoehorned together under the folklore. The unexplained happenings, such as the sightings, vocalisations and stock kills, all coalesce into the phenomenon of the big cat. But as a sceptic, he says he would love to be proven wrong.

“What you have in Australia is 200 years of repeated, consistent sightings of cat-like predators, but no smoking gun,” he says. “But I fully encourage people to go out and get that evidence.”

Dr Waldron is often asked for insight on sightings, and is approached with potential findings. He considers these photos and video, from near Nundle, NSW in 2018, some of the best he has seen – especially because it provides scaling with the fallow deer in relation to the tree.

Video sent to Waldron, Nundle, NSW in 2018.

The closest to primary evidence of the existence of big cats in Australia was documented in a 2012 report by the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment, that detailed all the possibilities of big cats in the state. The most compelling being a scat that was found in Winchelsea in 1991, which was found to be almost identical to leopard scat.

Although there’s been no proper first-tier evidence, the amount of sightings and reports make it difficult to fully disregard the notion that there are or were big cats in the Australian bush. Maybe they were here but over time they have become fully extinct? Or, maybe they always have just been oversized feral cats? We may never know. But what we can assume is the legend of the panther will always be entrenched in Australian folklore.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Article: Ashton Tresidder is a third-year Bachelor of Media and Communication (Sports Journalism) student at La Trobe University. You can follow him on Twitter @ashtom_tres

Photo: Black Panther, by Rute Martins of Leoa’s Photography available HERE and used under a Creative Commons attribution. The image has not been modified.