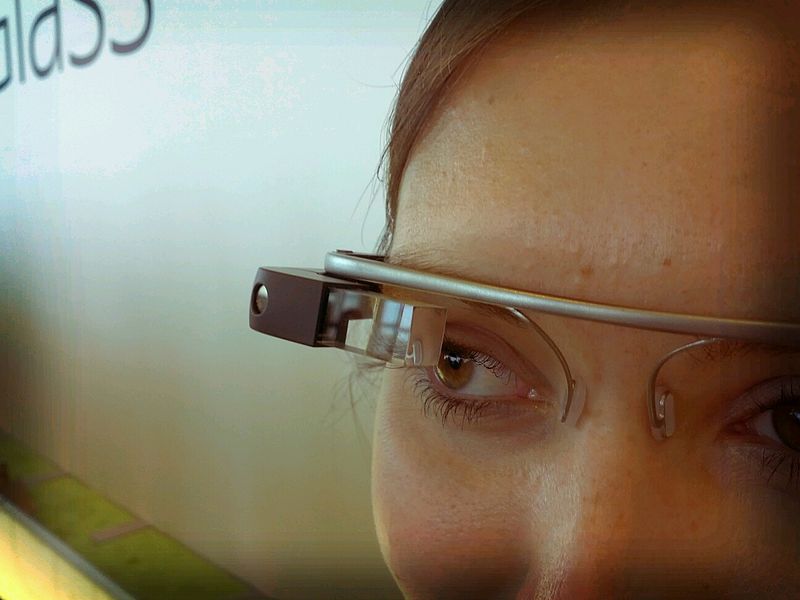

The internet giant’s latest technological product, which was demoed earlier this year, is an augmented-reality, artificially intelligent headgear: mounted on the right is a small computer monitor and screen (without interfering your view) that displays information and notifications.

The final product may also be able to integrate with an existing pair of glasses or contact lenses.

The idea is to provide information relevant to your surroundings, meaning that the product has a level of self-awareness. Appearing in front of you whenever you need it, all without searching for and fiddling with cumbersome gadgets.

According to Steve Lee, Google’s lead product manager, Glass is a ubiquitous and unobtrusive eyewear communication, which may one day make PC and handheld devices obsolete.

‘What may take 30 to 60 seconds on a phone will instead take two to four seconds on Glass,’ he says.

‘Past wearable computer projects that people have seen likely conjure up something that gets in your way and blocks your vision or senses. That’s actually counter to our project goal. Everything around our design is exactly the opposite of that.’

Although augmented reality and wearable computing isn’t new, Google’s financial clout and investment and efforts in almost everything technological means Project Glass may be the first to be popular among journalists and mainstream audiences.

Project Glass’ services include text, MMS, phone calls, social networking with Google+, a navigation system, and a camera that can shoot stills and videos.

For journalists, this product could mean wearing (instead of carrying) journalism tools, freeing them to report—faster than ever before—society back to itself.Imagine the potential benefits: a more centralised place for data collection and inquiries, faster information display, safer field reporting (eg war and crisis), performing online searches without fretting over handheld devices or hard copies, more events and crises being live streamed from multiple perspectives.

Like all innovations, however, there are bound to be concerns about Project Glass’ impact on journalism law, practice and philosophy.

Going from web history to recording what you see and do is a huge leap of faith, so how will Project Glass affect privacy issues, such as confidentiality of information and sources?

As The Atlantic writer Navneet Alang says, ‘There is nothing inherently wrong with the world Google imagines: checking in at a coffee shop, texting with friends or video chatting with a partner. In as much as digital can place these in front of us, this is good. But Google has always had its own ends for how it has organized information, and other companies do too.’

How will it affect media organisations’ business models and traditional journalism principles?

Should journalists trust the information that Project Glass’ artificial intelligence provides?

How will it shape debates about editorial issues such as immediacy versus accuracy related to Twitter and other online platforms?

Will citizen journalists become the majority?

As for Google’s advertising programs, TechCrunch reports that Google co-founder Sergey Brin says there are no plans to integrate advertising into Project Glass. That however, doesn’t negate the opportunity to data mine for non-advertising purposes, such as research and development.

In the long run, however, could constant, on-demand augmented reality (if adopted by the masses) dissolve journalists’ face-to-face interactions with human sources?

It’s still early days, but the potential benefits of technology like Project Glass to journalism are noteworthy.

The product’s unique selling point is that communication occurs best when technology gets out of the way.

But if the invisible takes hold, then will journalists live more robotic lives and principles of journalism become slavery of gadgetry and computers instead?

Tou Vue is a Master of Arts (Journalism) student at Charles Sturt University and an editor at Media Dynamics, a Brisbane-based publishing firm.