Football transfers have become an extension of the entertainment offered on the pitch; a behind-the-scenes soap opera of wheeling and dealing.

Despite the widespread attention transfers draw, the intricacies of this often complex process are generally reserved only for those working on the deals.

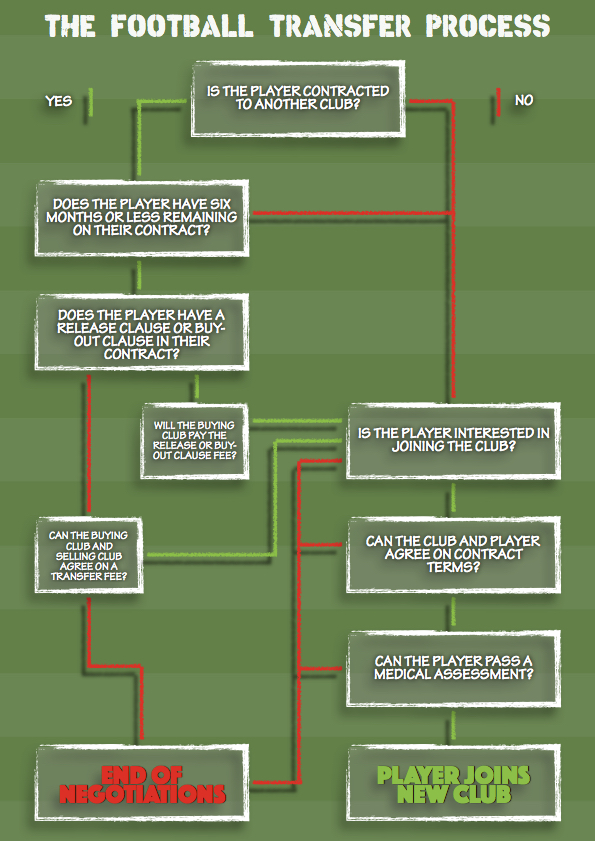

President of the Australian Football Agents Association Peter Paleologos says a transfer is ultimately a negotiation involving three parties.

“A transfer is between two clubs and a contracted player. You’ve really got to get the club’s consent and the player’s consent. It’s two processes in essence,” he tells upstart.

“A fee has to be agreed first for a club to talk to any player. The selling club wants to know that the [buying] club can afford them and how they’re going to structure the transfer – they might not get all the amount first up.”

In certain cases the requirement for buying and selling clubs to agree upon an appropriate transfer fee can by bypassed due to the terms of a player’s contract.

A release clause specifies the minimum offer a selling club must accept for a particular player if one is stipulated in their contract.

For example, if John Smith has a contract with Club A containing a release clause fee of $500,000 and Club B bids anything less, Club A can reject the offer if they do not want to sell.

However, if Club B are willing to pay $500,000, Club A must allow Smith to speak with Club B if he wishes to do so.

Buy-out clauses are different to release clauses. This condition grants a player the right to terminate their agreement with a club by paying a predetermined fee.

In practice, however, if a club wants to sign a player who has a buy-out clause in their contract, it will provide the amount required to trigger it.

Approaching a player without the consent of their club (also referred to as tapping up) is somewhat common – but clubs must take extreme care to avoid breaching contract rules.

Approaching a player without the consent of their club (also referred to as tapping up) is somewhat common – but clubs must take extreme care to avoid breaching contract rules.

“It is [legal] in the sense that they may do it in a way where they have an agent who represents the club to do the research. They may not do it directly, because in a sense if they do it unilaterally, that could be seen as illegal in certain countries,” Paleologos says.

“A lot of times if you’re tapping up [illegally], it could end up in deduction of points, transfer embargoes or fines; especially if you force a player to terminate their contract unilaterally.”

Free agents and players with less than six months remaining on their current deal are allowed to negotiate with clubs at any time – even outside the transfer windows set by FIFA.

Once all the requirements to speak with a player have been fulfilled, Paleologos says the buying club must consider a variety of criteria when negotiating his or her employment contract.

“It’s salary, they look at training history, injuries, if they’ve been an international, attitude. There’s also another contract they look at if the player’s got image rights.

“The agent wants a slice of action, too, so that inflates the salary. The club that’s purchasing the player will have to deal with clauses like performance bonuses.”

Legally persuading a club to sell is often the most onerous stage of the transfer process, but Paleologos says the buying party still has work left to do even after they gain access to the player.

“If the player says I want this much, sooner or later you come to a point where you say okay, but it’s these other factors.

“Image rights are becoming the most difficult to bed that down. But I think if you know the release clause, then you’re halfway there. Obviously the player also has to say yes [to moving clubs] – that’s the most important thing.”

A comprehensive medical assessment is often the final hurdle before a player can put pen to paper with a new club, but they do not always go according to plan.

“In Europe, especially a lot of the Spanish and English clubs, they’ve got very thorough tests. You might be super fit, but they may find something that you didn’t even know existed,” Paleologos says.

In July 2016, former Sydney FC midfielder Chris Naumoff was forced to retire at 21 years of age due to a genetic heart condition discovered during a medical with Numancia in Spain.

A player’s nationality and passport type can also affect whether a transfer goes through or not, particularly in the United Kingdom.

“At the moment, if you’re an EU [European Union] player, you can play in England or the UK. But if you’re not an EU player, you have to be quite up there in terms of being a professional player, but also a national team player,” Paleologos says.

OFFICIAL: Simone Zaza has completed a £24m move to West Ham from Juventus. #WestHam pic.twitter.com/jxa6EzIUVh

— Betting Directory (@BettingDirector) August 28, 2016

Whether a player is unhappy at their club or a manager wants to declare interest in signing someone, the media can act as an important catalyst for manufacturing a potential transfer.

“Agents use the media as a ploy to say this player is interested in coming to A-League, interested to go to Chelsea or whatever. There may be no interest from clubs, but what it does is let you actually put it out there,” Paleologos says.

“A lot of players can tell their agent: ‘I’m interested in this club, what do you think?’ Or clubs can speculate and say we’re interested in these types of players, and they build up on that. The media loves that, especially in England and Europe.”

Paleologos says while the deals between clubs and players at the highest level draw most of the attention, massive transfer fees and eye-watering salaries misrepresent the financial workings of the football industry at large.

“If you look at the salary of a lot of the players that have been transferred, only about 4 per cent have been over USD$1 million – that’s not a lot. Nearly 50 per cent of players [worldwide] are earning less than USD$30,000 [as of May 2016].”

Luke Karlik is a third year Bachelor of Journalism (Sport) student at La Trobe University. Follow him on Twitter: @lukemkarlik

Luke Karlik is a third year Bachelor of Journalism (Sport) student at La Trobe University. Follow him on Twitter: @lukemkarlik