On 28 October 1628, the East India Company ship, Batavia, led by Commander Francisco Pelsaert, set sail from the Dutch port of Texel for Batavia, now modern-day Jakarta. Loaded with chests full of coins and building materials, the ship carried approximately 340 people, two-thirds of which were sailors. Another 100 were soldiers and the rest were civilians seeking passage.

A little over a year later, more than 200 of those passengers would be dead. The majority—many of those women and children—had been murdered on a chain of islands just off the coast of Western Australia.

Despite being a series of events that not only contain gruesome murders and a psychotic antagonist, but also led to Australia’s first European-built structures, the tale of the Batavia shipwreck is a largely unknown part of our country’s past until recently. In fact, a 2018 SBS documentary described the tale as “the craziest Australian horror story you’ve never heard of”.

Kieran Hosty, a manager at the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) and an archaeologist who has worked at Batavia excavations, says that while the story has not become widely known across the country, it is well-known among certain communities and those raised in Western Australia.

“I’m from Western Australia so I grew up with the story of the Batavia and the mutiny,” he tells upstart.

So, what happened on the Batavia that would leave over 200 people dead?

According to Hosty, the majority of the passengers were murdered at the hands of a group of their shipmates.

“Intrigues and jealousies broke out and a band of mutineers, led by some of the wealthiest and most influential people on board – including the second and third in command – decided to take the ship, the treasure and the younger women, and dispose of the rest,” he says.

This plan was hatched by the second in command, a man by the name of Jeronimus Cornelisz, who wanted to take the ship and the coins and to form a crew of pirates with several other passengers with which he hatched his plan. The rest of those on the ship were to be killed and thrown overboard.

However, Cornelisz’s plan was foiled before he could make his move to take the ship when, according to an article by the Western Australian Museum, strong winds, a lack of knowledge of the ship’s longitude and night-time conditions drove the ship onto Morning Reef, approximately 60km west of Geraldton in Western Australia.

The ship was lodged and taking on water. Most onboard were evacuated to nearby islands. However, 70 passengers decided to remain on the slowly sinking ship with the treasure and materials. This, of course, included Cornelisz and his rebels.

Commander Pelsaert led the group of evacuees to what is now known as Beacon Island and the aptly named Traitors Island.

Arvi Wattel, an art history lecturer from the University of Western Australia, who has written about the Batavia, says that the ship was carrying “twelve chests of silver and gold coins”, which is worth roughly $20 million today.

Once Commander Pelsaert was off the ship with the evacuees, Cornelisz and his men went after the treasure.

“Emboldened by drink and desperation, they [Cornelisz and his men] forced their way into Pelsaert’s quarters and broke open the upper merchant’s sea chest,” he tells upstart.

The chest contained Pelsaert’s personal collection of medallions, which the rioters distributed among each other as booty.

However, in a detail that Wattel finds fascinating, the men threw the bounty into the sea, exclaiming, “there lies the rubbish, even if it is worth so many thousands”. This is a part of the story that history has never been able to explain considering the treasure on board was an initial motivation for taking the ship.

Eight days later, the Batavia finally sank, causing Cornelisz and the rest of those who stayed on board to join the other evacuees on land. This would prove a tragic turning point for those already on the islands, as this led Commander Pelsaert to embark on the rescue mission. He took most of the soldiers and a small boat from the Batavia and continued the journey to Jakarta. Hosty says that the remaining 40 men – some soldiers – as well as the women and children fell “prey” to the second in command.

Meanwhile, Cornelisz had secured the loyalty of his original mutineers with a promise that they would get “the pick of the women and a cut of the treasure”, and promptly disposed of anyone who could try to challenge his authority.

The plan remained the same: to take the next ship that sailed by and become pirates.

To do this, Cornelisz thought it would be best to separate the group, removing those that may challenge his authority, and sending the strongest and most capable passengers away. He sent approximately 45 men, women and children to Seals Island under the false pretence they should find water there, believing they would either drown on the way over or dehydrate.

He then instructed the remaining soldiers, led by Weibbe Hayes, to explore another island now known as West Wallabi Island with the same goal in mind. Finally, Cornelisz sent any remaining able-bodied men or boys on errands with his conspirators, who would then drown them in the sea.

A couple of days later, Cornelisz noticed movement at Seal Island. It appeared the first group of survivors he had sent to die were still alive. To speed up the process, he decided to send men to Seals Island to kill them.

“The mutineers went on a rampage,” says Hosty.

It was on this rampage that over 120 of the victims would be murdered. The survivors on Seal Island, and the women, children, the elderly and the sick who were left on Beacon Island with Cornelisz, were all butchered. But not long after the murders, Cornelisz spotted a smoke signal from West Wallabi Island, where he’d sent the soldiers. Not only were they still alive, but the signal meant they had also found food and water.

“Every villainous story needs a hero and in the case of the Batavia, it was a soldier named Weibbe Hayes who led a group of loyalists against the mutineers,” he says.

Hayes and his men, contrary to what Cornelisz had hoped, had discovered both water and food on the island. Natural limestone formations caught rainfall and Tammar wallabies habituated the island, which they caught for food.

On Seal Island, a small number of people had survived the massacre and were in hiding when they also spotted the smoke signal from the soldiers. Knowing that this meant Hayes and his men were alive, the Seals Island survivors fled to West Wallabi Island and informed them of what had happened.

“Hayes prepared his island for an attack from the mutineers by building several stone forts,” says Hosty.

“Several attacks by the mutineers occurred, but they were all fended off.”

On one attempted attack, Hayes and his men managed to capture Cornelisz. The exact amount of time they held him prisoner is unknown. However, it is believed that Commander Pelsaert arrived with a rescue ship only days after Cornelisz’ capture and was quickly informed of what had transpired.

Pelsaert’s punishment was quick and harsh. He ordered the condemned have their right hands cut off and then hung. Cornelisz had both his hands removed before being put to death. The executions occurred on Beacon Island on 2 October 1969, a little under a year from when Batavia first set sail.

Afterwards, more of the lower-level mutineers would be taken to Jakarta for trial. They were all found guilty and executed. By the time the story of the Batavia would end, only 116 of the initial 340 people who set sail from Texel on that fateful day would still be alive.

Over 300 years later, archaeologists have found most of what remains from the ship on the chain of coral islands and in the ocean.

“They did a very large excavation in the 1970s where they retrieved most of what was still left in the sea,” Arvi Wattel says.

“They still find belt buckles and smaller items, which makes sense because they buried the people that they killed. But they wouldn’t bury them with precious material.”

Excavations still take place on the islands today, says Kieran Hosty, and the remains of victims are still being exhumed. The site is still visited regularly by historians and archaeologists from both Australia and the Netherlands.

“This work has involved the recovery of skeletal material, in particular a mass grave.”

The tale of the Batavia is hard to fathom. It’s also hard to believe that so little of a story that ended in the death of 120 innocent men, women and children, is known outside of Western Australia. Most of the victims’ remains are still on the islands, alongside the structures built in those days, serving as a reminder of the tragedy that unfolded.

“Not only did the Batavia shipwreck lead to the construction of Australia’s earliest European built buildings, [but] it also led to the construction of Australia’s earliest prison and its earliest gallows,” Hosty says.

“The rest, as they say, is history.”

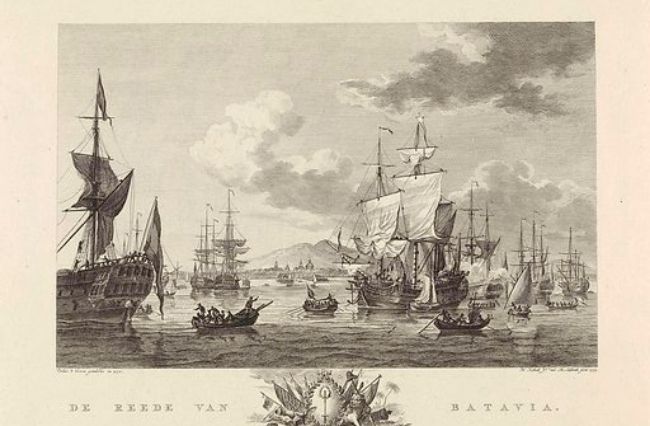

Cover photo: Ships on the roadstead of Batavia by Rijksmuseum available HERE and used under creative commons attribution. This image has not been modified.

Photo 1: The Fort by Rupert Gerristson available HERE and used under creative commons attribution. This image has not been modified.

Photo 2: Seals Island by Guy de la Bedoyere available HERE and used under a Creative Commons licence

Article: Jordan McCarthy is a second-year Bachelor of Media and Communication (Journalism) student at La Trobe University. You can follow him on Twitter @JordoMc85