There has been much anxiety during the past fortnight over Labor’s proposed reforms to electoral funding, but according to Stephen Luntz, Greens party electoral analyst and partner at Above Quota Elections, we’ve seen it all before.

“The number of people who are aware that it exists – and we’ve had money for political parties since 1984 – is very small. It gets fussed when they look at increasing it, but within a few moths, people have forgotten,” he says.

So, is there a more-pressing issue for Australians when it comes to voting?

Luntz says that there disparity between what is a commonly-held perception and the reality of the matter: “My position personally – and this is not speaking for either the Greens or Above Quote Elections – is that we actually make legally explicit what is the situation at the moment: which is that it is not actually compulsory to vote.

“It’s compulsory to turn up at the polling booth and get your name crossed off. If we actually make people fill out a valid vote, that for me would be an infringement on democracy; that people are entitled to not vote for any politician.”

As it stands, approximately four per cent of votes cast are listed as an ‘informal’ one. According to Luntz about half of those are deliberate, while the other half come from good intentions. He says that there is a better alternative out there: “I think we shouldn’t have this law that says its compulsory to vote when that cant be enforced and would be undesirable to be enforced.

“Bringing the law into line with what actually occurs would be a better practice: to say ‘you have to turn up, you have to get your name crossed off, but if you don’t want to vote, that your right’.”

While the theory of dropping voter numbers may be hard to test, The Australia Bureau of Statistics has documented voter numbers in local, non-compulsory elections compared with their compulsory counterpart. In Victoria and New South Wales, where it is compulsory, the 2008 election had a turn out of 76 and 83 percent, respectively. A year later, in Tasmania and Western Australia, where local government elections aren’t compulsory, there was a turn out of 56 and 33 percent respectively.

Although hard to pin-point the reason, Luntz does say that getting rid of compulsory voting would have an impact. “If we had voluntary voting and kept the system we’ve got, then turn-out would drop, but not by as much [when compared to the USA].”

The US Census Bureau and the Department of Commerce have compiled a table of voter number in the US. It shows that for the 2008 presidential election, 61.8 per cent of eligible people voted. The number has remained steady since 1996, where it sat at 58.4 per cent. So, should these numbers be alarming to Australians?

With The USA as the prime example for what can happen in a non-compulsory voting system, Luntz raises the point that the Australia and America should not be compared: “Part of the reason voting is low in America is because they have it on Tuesday and many people are working.”

He goes on to say that there would be a drop in numbers, but not one to the standard of America

Apparently there are numerous cases of Republican bosses not allowing Democrat staff leave to vote; according to Luntz, this practice is well-established. That said, the Texas Election code does state that an employee is entitled to time off to vote, on the proviso that they do not have two hours outside of work to do so. This is similar for other states. PayScale documents the applicable rulings.

This is not the only difference between the two countries. On polling day in Australia, there is access to polling booths. For most, you needn’t travel past your local kindergarten. By contrast, Luntz says that this infrastructure is missing in the States: “You’ve got situations where there’s very small numbers of polling booths in small areas and people in one part of town have to queue for five hours to vote whereas for people in another part of town, there’s no queue. Funnily enough, those parts of town tend to reflect whoever is in control in the state.”

As the election campaign begins to gather momentum, the September 14 election may be seen as both facilitating democracy and infringing upon it.

Adria De Fazio is a third-year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University, and a staff writer for upstart. Follower her on Twitter: @adriadf

Adria De Fazio is a third-year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University, and a staff writer for upstart. Follower her on Twitter: @adriadf

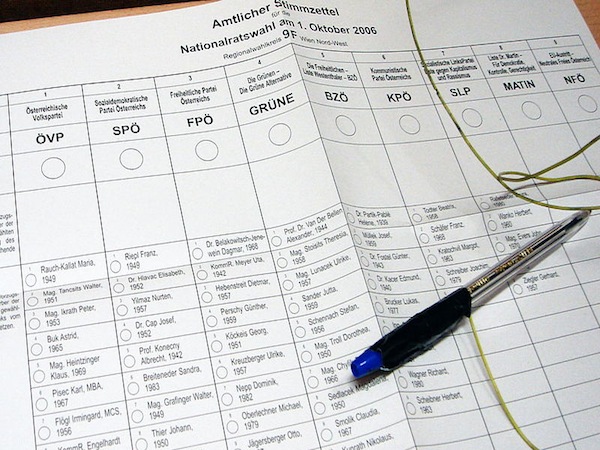

Photo: Hermann A.M. Mucke