“You’re blonde, and people think blondes are stupid.”

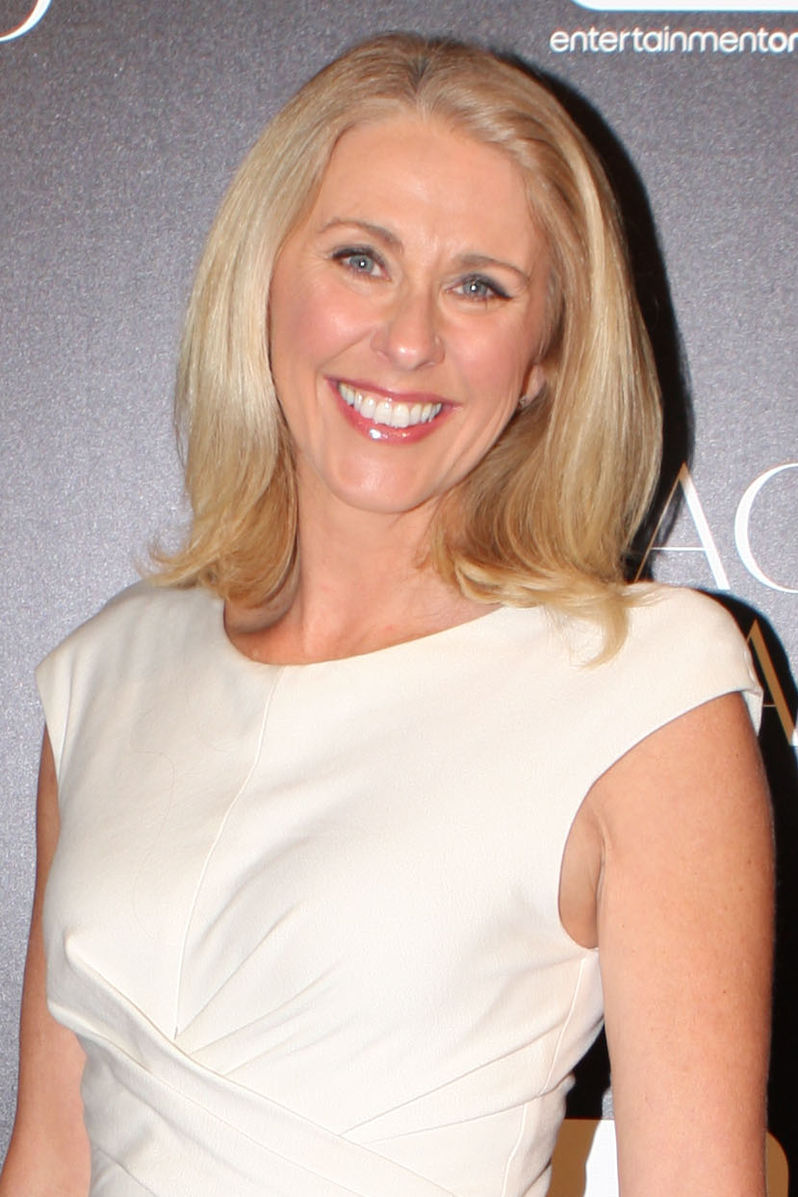

This is what Australian journalist Tracey Spicer’s boss told her when she asked, after a year of working in country television, if she would ever make it in the “big city”.

So this is what she did.

“I went out and bought a $2 box of Clairol and dyed my hair red,” Spicer tells upstart. “Not long after, I got a job in the top-rated TV newsroom in the country: Channel Nine in Melbourne. I have no idea whether my hair colour played into that, but I was encouraged to keep my hair red for almost a decade afterwards.”

According to many in the industry, Australian newsrooms have had a historically nasty habit of being very particular about who they put in front of cameras. For many women journalists, the recent ABC series, The Newsreader, about a newsroom in the late 80’s and early 90’s, has rung true to real-life experiences. Nicole Chvastek, host of ABC Victoria’s Statewide Drive program tells the ABC that particularly when working at commercial stations, a solid skill set was not enough.

“One of my mangers said to me ‘can you make them want to f*** you?’,” she told the ABC.

Spicer, who in her long career has worked for ABC TV and radio, Network Ten and Sky News, says she has always been aware that her performance has been judged predominately on how she looked rather than her actual skill. She is also aware of the double standards. The 54-year-old journalist says she faced many workplace experiences over her career that her male colleagues did not have to endure, including focusing on her appearance.

“An inordinate amount of time was spent on getting my clothes, hair and makeup a certain way. This was not an expectation of my male colleagues and or co-hosts,” she says.

The double standard can also extend to age. Lisa Cox, disability affairs officer at Media Diversity Australia, who has an extensive background researching body image and the aesthetics of news readers, says there’s a huge disparity in age and image expectations between genders

“Men can keep working into their twilight years. Women get grey hair and that’s a no, no. Men can put on weight, with women it’s ‘oh she has let herself go’,” she tells upstart.

However, there does seem to be a consensus that things are changing. Spicer recognises that, what she calls the “beauty bonus” and “beauty penalty”, are less evident than they were in the past. However, she says that at commercial stations particularly there is still a great deal of work to be done.

Accounts of former broadcasters tell us that if you’re a woman and you are not of a certain aesthetic, life as a broadcaster can be very difficult. You are very frequently judged based on your appearance and not your skill. To make things worse, social media has given almost everyone a licence to say what they like about those they view reporting the news. This too has its impacts.

“Every time I received a letter, email or social media comment about my appearance, it eroded my confidence,” Spicer says.

Diversity is another issue. There is currently a narrow range in the types of faces and bodies that get to be on screen presenting news and this extends beyond gender. Overall, it is hard to get people who look “different” on screen, Cox says, because lots of people don’t actually fit the strict “beauty guideline for news readers”.

“Seeing a woman in television over forty is really rare. Seeing a woman above a size 12, or someone wearing a hijab, or someone with a disability, or someone with a different skin colour, there are so many things to do with appearance that we need to overcome,” she says.

Cox herself has disabilities that she acquired after a stroke. She uses a wheelchair and she says people in her life, like her nieces and nephews don’t bat an eyelid, it but when she goes out to places like shopping centres, kids often get scared by her because they don’t see people with disabilities doing normal things, like shopping or presenting the news.

“Too many people are those scared kids in the shopping centre,” she says.

Who we see on television is meant to be a mirror of who we are as a country: from the anchors to those reporting the news. To date, statistics show that Australian TV news doesn’t do a very good job of reflecting Australia and its unique population.

A report released last year, titled “Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories?”, found that more than 75 percent of presenters, commentators and reporters have an Anglo-Celtic background, yet only 58 percent of Australians are of an Anglo-Celtic background. Meanwhile, people of non-European background make up 21 percent of the general Australian population, but only nine percent of presenters, commentators and reporters are people with a non-European background.

Part of the report included a survey element where media industry employees were asked about perceived barriers in the industry. 79 percent of respondents believed that culturally diverse people experience more barriers when attempting to access jobs in front of the camera.

This is not the first time we’ve heard this. Waleed Aly dedicated his 2016 gold Logie win to “people with unpronounceable names like Waleed”. Aly has become a well-known TV personality in Australia, but in his acceptance speech he spoke about racism in the TV industry and the way he always thought things like Logies “were for other people”.

The same year Noni Hazlehurst was only the second women ever inducted into the Logies Hall of Fame. She highlighted in her speech the “snail-like pace” in which the TV industry accepts women and non-Anglo-Saxon people.

However, there is nothing to suggest that audiences don’t wish to see greater diversity in appearances on their news bulletins. In fact, the figures show quite the opposite to be true.

Increasing diversity is part of developing a strong business case. In 2020 global management company McKinsey & Company found that companies with both gender and cultural diversity financially outperformed those who did not. This confirms a trend that the company have been tracking since 2015: consumers want a better reflection of their communities.

TV networks are seriously behind advertisers and corporate marketers when it comes to this. One respondent in the “Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories?” survey recognised that networks are not responding enough to audience’s demand for less rigidity in appearances.

“I mean, obviously [advertisers and marketers] are using it for commercial gain but … if they can do it, then the rest of the media industry should be doing it,” a research participant said.

“The research clearly shows that audiences want to see a diversity of people on their screens,” Spicer says.

The power is falling more and more to the consumers to dictate what and who they want to see on their daily news bulletins. Cox says that with the development of streaming services and so many different choices when it comes to getting our news, consumers will flick to what they want to see and what aligns with their values.

“It’s not just a case of ‘get what you’re given’ anymore. People will flick to see the size 14 woman in a hijab,” she says.

However, Spicer says that now it’s the executives who make the decisions about who is on camera who need to come to the party.

“Some executives don’t even think it is a problem. This is mainly because of the lack of diversity in the senior executive roles,” she says.

In 2018, Lee Lin Chin, popular SBS news reporter, announced her resignation from the broadcaster after 30 years. She attributed her resignation to systematic workplace issues at the broadcaster, including a lack of diversity in management. Since 1980, when she began at SBS, Chin had provided a point of difference in the homogeneous news-scape and has been a rare example of not only an older woman reading the news but an older Asian woman reading the news.

Isabel Krug, co-leader of University of Melbourne’s Physical Appearance research team, says who we see on the news can impact us in a similar way to other media.

“We have a perception of what is attractive because we are constantly bombarded with it,” she tells upstart.

“We do unfortunately judge people based on their appearance, it is the first thing we see and we compare ourselves to people who are more attractive than we are,” she says.

There is also research that shows that the way news presenters dress is important to the audience’s attention span and how much information they retain.

Research also indicates that there are certain things about a presenter’s look that will influence how audiences experience a news bulletin.

“They [reporters and presenters] are giving critical information so they need to look trustworthy,” Krug says.

However, most of this comes down to distraction and not the actual appearance of the person in front of the camera.

A 2017 study found that a newsreader’s choice of clothes, accessories, hairstyle, make-up and facial expressions can be sources of distraction or attraction to audiences. This is something Dr Christopher Scanlon, journalist and senior lecturer in communications at Deakin University, teaches students. Like any job, there is an expected way you should look when you show up for work.

“I teach them things they can control. Shape your appearance so it is not distracting. You don’t want to be wearing clothes or makeup or accessories that are going to distract the audience,” he tells upstart.

But Scanlon also says that it is possible for everyone to work in broadcast, no matter what you look like it is becoming more and more common for appearance to not matter at all because news outlets are utilising entire packages where the journalist is never even seen.

“There has been a move away from doing that piece to camera or the stand up, of course it’s not everywhere, but in a lot of reports you won’t see the reporter,” he says.

“If you talk to some broadcast educators and journalists, they hate it [having the journalist in the report] because they say it makes the journalist look like the star of the program, it is kind of that ‘anchor man’ idea they play with in the films, people find it cliché and unnecessary.”

Scanlon also notes that audiences are increasingly seeking out programs that feel “real” with people reading the news who look like them, who look like they exist in the real world. He believes a large part of this search for authenticity comes as platforms like YouTube and Instagram change our visual grammar.

“Not that broadcast is going to look like Instagram or YouTube but I think we are seeing more of that informality, more of that authenticity because it is what audiences increasingly expect,” Scanlon says.

Cox also believes that while the commercial media landscape still looks very cardboard cut-out, some networks are trying.

“I think some are fearful of putting a foot wrong.”

“But there is a lot that can be done,” she says.

Krug says that beauty standards change over time, so it wouldn’t be surprising for the next few generations to bring a whole new, much more authentic “look” to the media.

“By providing more variety of people presenting, of different shapes, different sizes, different heights, different ethnic backgrounds, that would make a difference to what we view as attractive,” she says.

Spicer says that for aspiring journalists, things could look very different soon.

“Let your ability and intellect shine,” she says.

Article: Brittany Carlson is a third- year Bachelor of Media and Communications (Journalism) student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter @media_brittany.

Photo: Al Jazeera English newsreader by Paul Keller is available HERE and used under a creative commons license.