When Leah Ruyter was just six years old, she was told she was going to die.

“It was traumatic. When you’re so young it’s hard to comprehend something as significant as your own death,” Leah tells upstart.

Ms Rutyer was born with a hole in her heart and absent pulmonary valve syndrome. She underwent her first of three open heart surgeries when she was just months old.

After years spent in and out of the Royal Children’s Hospital, Ms Rutyer was told that to increase her chances of survival, she would require a tissue transplant, to replace her pulmonary valve.

Just after her seventh birthday, she received her second chance at life.

“Back then if I hadn’t have received the donor valve I would have died. They thought there was a high chance I was going to die anyway,” Leah says.

“I always remember telling everyone when I was younger that I have a 14-year-old boy’s heart valve in me, like he saved my life. He really did save my life. If I hadn’t have received that valve, I would not be here and I wouldn’t have my daughter.”

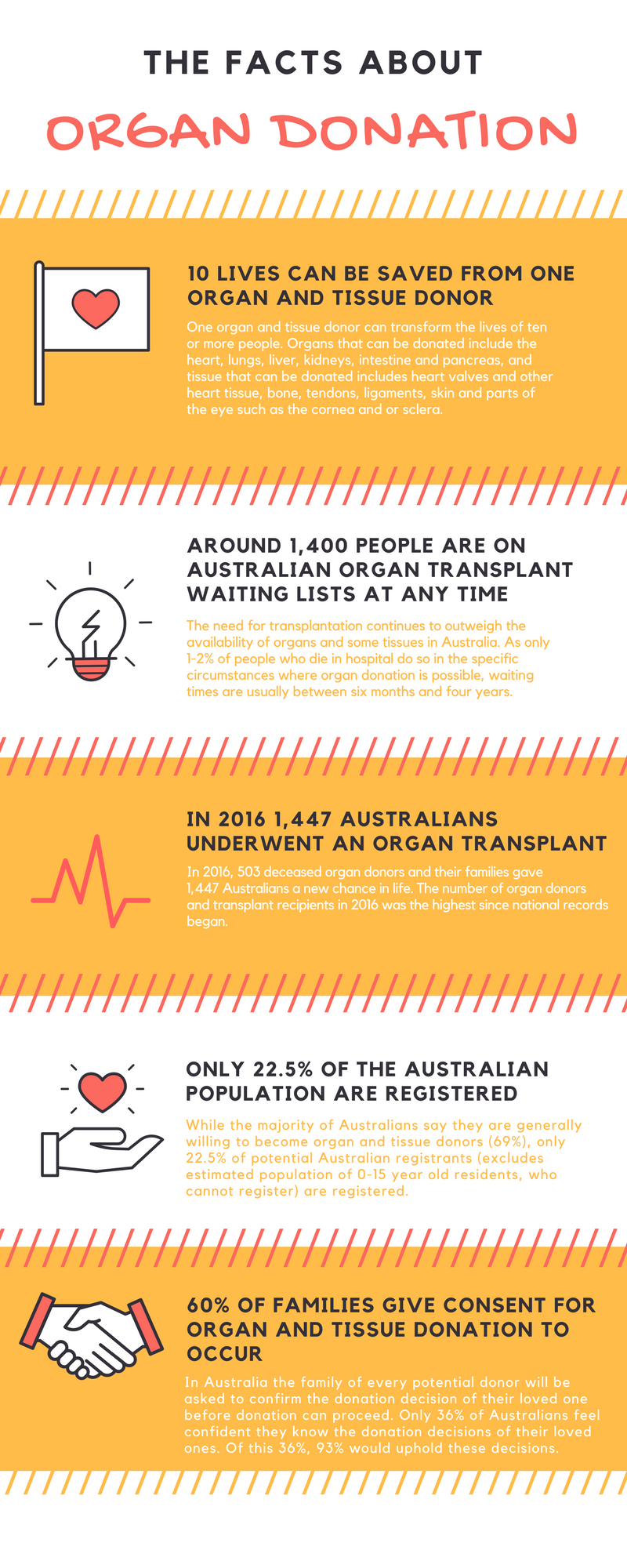

While donation and transplantation outcomes have increased substantially since 2009, the number of Australians legally registered on the Australian Organ Donor Register remains quite low.

Just 22.5 per cent of eligible Australians have legally registered their consent with the Australian Organ Donor Register, as of 31 August 2017.

Prue Gildea from Donate Life, an agency of the Australian Organ and Tissue Authority, says that while many Australians are generally supportive of the act of organ and tissue donation, few legally register their support.

“Registration regularly comes up as something that they’ve been meaning to do or it’s something that they’ve thought about, but haven’t gotten around to doing,” she tells upstart.

“We know community support for the idea of donation is much more like two in three people, while eight in ten believe it’s important to register. So there seems to be a gap between people being supportive of donation and actually doing the action that is to register.”

Ms Gildea believes that registering your decision can generate important discussion between family members, which can ultimately help to increase Australia’s donation rate.

“It often raises questions in families about what other family members want and what their position might be on the issue [of organ and tissue donation],” she says.

“We always say that registration and conversation are the two most important things that people can do to help raise the donation rate in the country.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWAKTsqLTnA&w=560&h=315]

On July 2 2008, the Australian Government announced a national reform program to implement a world’s best practice approach to organ and tissue donation for transplantation.

The national reform program aims to increase the capability and capacity within the health system to maximise donation rates, and raise community awareness and stakeholder engagement across Australia, to promote organ and tissue donation.

Deceased organ donation has more than doubled since the program’s implementation, with 503 donors in 2016 compared to 247 in 2009. The program has also resulted in an 81 per cent increase in the number of organ transplant recipients (1,447 in 2016 compared to 799 in 2009).

While significant growth in organ and tissue donation rates has occurred as a result of the program’s implementation, the need for transplantation continues to outweigh the availability of organs and tissues.

In Australia, only 1 to 2 per cent of people die in hospital in the circumstances where organ donation is possible, while tissue donation is less limited.

Due to the fact that the opportunity to become an organ donor is so rare, it is especially important that willing Australians register their decision.

“We face a fair bit of criticism about what is considered a low donation rate but what’s not widely understood is that donation is a really rare opportunity,” Ms Gildea says.

“If people do fall into that 1 to 2 per cent, the best thing is if they are registered. It creates no uncertainty for family in that time, in a really stressful situation, often in a sudden death or a traumatic situation.”

In Australia, the family of every potential donor is asked to confirm the donation decision of their loved one before donation can proceed.

The Australian Government Organ and Tissue Authority says the most important factor in a family’s decision to donate is knowing the wishes of their loved one.

“Someone doesn’t have to be registered to become an organ donor. Sometimes people don’t understand that, necessarily,” Ms Gildea tells upstart.

“If somebody is registered and they’re in a hospital setting and they’re passing away, and their family has confirmation that they’ve registered a donation decision, that can often ease the burden of making the decision on behalf of that person.”

“Families statistically are much more likely to say yes when their loved one is a registered donor.”

In Australia, approximately 60 per cent of families give consent for organ and tissue donation to proceed after death.

In 2016, 1,041 families were asked to confirm whether their loved one was willing to donate their organs and tissue and 626 families consented to donation. Of those, just 142 did not proceed to donation.

Research conducted by the Australian Government Organ and Tissue Authority found that only 36 per cent of Australians feel confident they know the donation decisions of their loved ones.

Of these, 93 per cent say they would would uphold these decisions.

Having experienced the donation process first hand, transplant recipient Leah Ruyter now places a significant importance on registering with the Australian Organ Donor Register, and has proudly registered her own intent to donate, with the hope to save lives if the situation arises.

“If I can potentially save somebody’s life when I’m not here, then why not? There’s a lot of people against it but I don’t see why when you’re not here anymore. I don’t get it,” Ms Rutyer says.

“I think it’s extremely important for people to register. I’m here now because a family decided to save my life by donating their son’s organs and tissue.”

I’ve got a daughter and I’m living life to the fullest, and I wouldn’t otherwise have had the chance to. I wouldn’t have been able to experience life.”

Jessica Neale is a third-year Bachelor of Media and Communications (Journalism) student. You can follow her on Twitter @_jessneale

Jessica Neale is a third-year Bachelor of Media and Communications (Journalism) student. You can follow her on Twitter @_jessneale