In 2006 Google bought YouTube for $1.65 billion.

Little did they know that one year on they would be defending themselves in one of the longest running court cases involving copyrighted material on the internet.

Media enterprise Viacom initiated legal proceedings in 2007, claiming that YouTube had breached copyright by allowing users to upload millions of videos online.

After two years of the lawsuit being contested in court, a Federal judge ruled that YouTube was protected from any legal ramifications under Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

Viacom then appealed this decision, seeking for another hearing in an effort to prove that YouTube knowingly published copyrighted material. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit accepted the appeal and granted permission for the case to be re-heard in front of a jury.

In April 2013, a Federal judge again found YouTube innocent of any copyright breach. Viacom has made known their intention to appeal this most recent decision, ensuring that YouTube is not yet in the clear. A summary of court proceedings can be found here:

The legal implications of the most recent decision has ramifications for both websites who source user generated content and third parties which resultantly may have their copyright safeguards breached.

Federal courts have now set a precedent that protects social media and other online service providers from breach of copyright under the safe harbor provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

However, in order to be protected under Section 512, these websites must:

(i) not have actual knowledge that the material or an activity using the material on the system or network is infringing;

(ii) in the absence of such actual knowledge, not be aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(iii) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to the material.

As outlined in the 2013 court proceedings, web generated content is increasingly rapidly and this therefore makes it difficult for sites to monitor every single piece of material on their server.

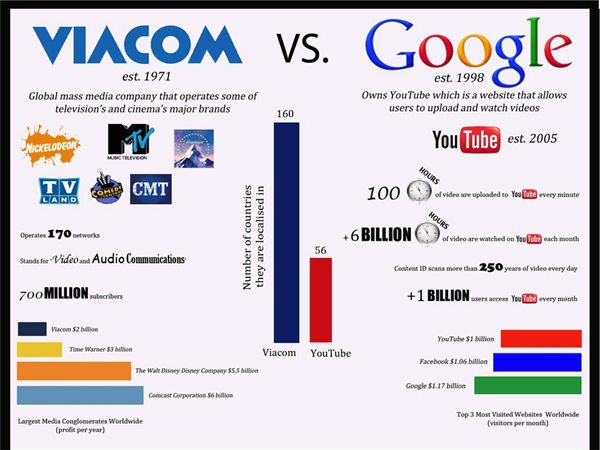

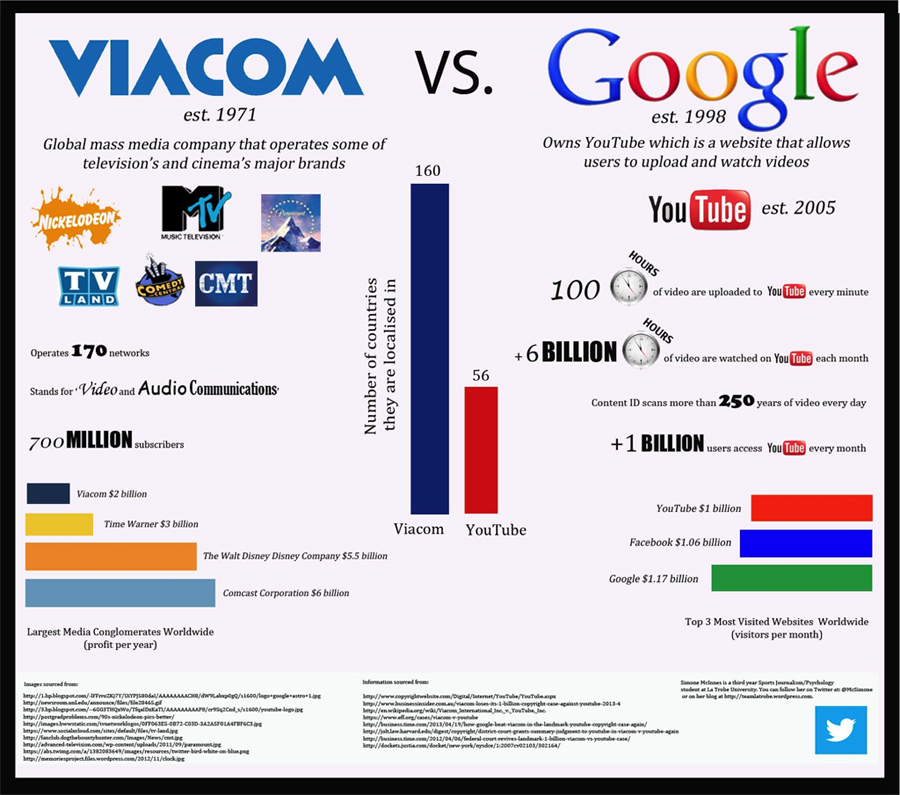

The article continues below the infographic. Click on the image for full screen view.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (1998) has sought to account for this by placing the burden on the copyright owner, stating that they must notify the website of the infringement before legal action can be undertaken.

As a consequence, while online service providers can put measures in place in order to identify copyright breaches, they are not legally obliged to delete infringing material unless they are aware of specific instances.

This therefore means that websites such as YouTube and other social media sites are able to continue circulating a vast amount of content without having to stringently rely on their internal systems to identify copyrighted material.

One article describes the most recent decision as a “license to steal”. Essentially, online distributors have been granted control over content, rather than those who created it; a move which has significant implications for content producers around the world.

This prompts the discussion of the ethical implications associated with distributing other people’s work. As Viacom stated in the early stages of the ongoing saga, YouTube is essentially gaining advertising revenue as a result of uploading material that does not belong to them.

While this would usually contravene the copyright fair use exceptions, the DMCA essentially excuses this behaviour. Therefore online service providers are also not ethically or legally obligated to delete material that has unknowingly been used to increase revenue – no matter how much revenue that content has created.

Another point that should be noted is that the recent decision has brought the DMCA in line with other legislation such as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Similarly, this section has granted online service providers immunity from being sued over the comments on their webpages from Internet users.

As with the DMCA, Section 230 has been criticised for removing liability of defamatory content but the courts are seemingly of the opinion that such legislation promotes growth within the online community.

The dominance of Google has become known to an even greater extent over the past six years, and the sheer number of resources and revenue that Google acquires annually means that smaller companies simply cannot compete with the social media giant.

The amount of unsuccessful legal actions taken against Google after Viacom initiated the first complaint is evident of this fact. Some even go as far to suggest that Google’s supremacy is making the industry ‘anti-competitive’.

This means that journalists producing content for websites are essentially creating content for free, which begs the question as to what the future holds for the industry as a profession?

In conclusion, while it is evident that laws need to be continually updated in order to keep pace with the changing online landscape, content producers also need to be protected so that their rights are not violated.

While the DMCA and the precedents set out in the Viacom vs. YouTube case has provided much needed safeguards for protection against copyright breaches for online service providers, it potentially has serious implications for journalists who are trying to make a living out of their profession.

Simone McInnes is a third year Sports journalism/Psychology student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter at @McSimone.