Why is freedom of information an important democratic principle?

When you flick through the paper in the morning — or rather scroll through it — the articles you read have been affected by the country’s freedom of information laws. For something with a big impact, questions still exist about what can be accessed and under what circumstances.

The federal act is based on the presumption that every person has the right to obtain access to agency and ministerial documents, with some exceptions.

With citizen journalism on the rise, a clear understanding of the freedom of information legislation is essential. Any person, irrespective of their work or education can request access to agency documents — one doesn’t need to be a journalist to hold the government accountable.

What is freedom of information?

The Freedom of Information Act 1982 aims to promote national democracy, encouraging the public to form part of the governmental process. The act also seeks to give information ‘promptly and at the lowest reasonable cost.’ The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, which provides assistance and promotes awareness, guides freedom of information appeals.

Why do journalists need to know about freedom of information?

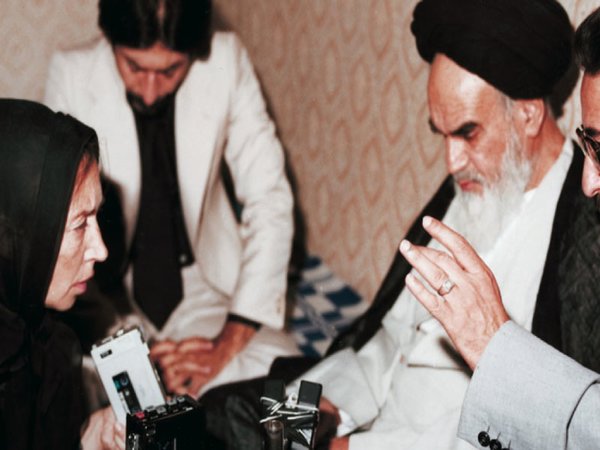

Transparency is a principle of all journalistic work: it is a guiding factor in what is written, spoken or seen. In an age where everything can be reached using our fingertips, getting the correct information is critical. The freedom of information legislation plays an important role in bringing about transparency — be it of government or a public figure.

The age-old debate still rages: privacy versus the public’s right to know. The arguments for both sides are well considered: the privilege to keep what is personal private, contrasted with the belief that public figures should be accountable to those who elect them.

The freedom of information laws seek to balance both sides of the debate. The laws provide the public with a framework in which to seek access, as well as ensuring the country’s safety is not breached.

Ian Richards, a journalism academic, contends journalists are guided by the justification of ‘doing the right thing.’ In Public Interest, Private Lives he says, ‘most of these journalistic defences derive from the notion of the greater good … the journalistic defence of the greater good rests on a common underlying view of the role of the media as democratic.’

The concept is also found in the MEAA’s Code of Ethics which states, ‘respect for truth and the public’s right to information are fundamental principles of journalism.’

Sean Parnell, Freedom of Information Editor at The Australian, says the legislation is vital to journalists, ‘the accuracy of news reporting depends on journalists testing the official line, digging deeper to better understand it’s an issue.’

The process

To obtain a document, you need to complete a request form. Alternatively, the request can be made by sending an email or letter to the organisation with the document. Following an amendment to the legislation, application fees no longer exist. Some charges do exist however, relating to application review, photocopying and inspection. More information can be found on the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s (OAIC) website.

As the states and territories have their own freedom of information legislation, the Constitution rids any ambiguity. Section 109 states, ‘when the law of a State is inconsistent with a law of the Commonwealth, the latter shall prevail…’

What documents can be accessed?

Most documents are available to the public, and a request is all that is needed to get the information. Australia is a country that prides itself on having a democratic, open government. This principle is something that underpins the Freedom of Information Act.

There are some exceptions, which mean that certain agencies or departments are not required to provide information. These include ASIO, the Australian Government Solicitor and the Office of National Assessments amongst others. Courts and tribunals must provide information relating to administrative processes if requested, but aren’t obliged to release information relating to court proceedings.

The act contains a clause that states an agency cannot be forced to disclose a document if the release of the document could jeopardise the nation’s security.

A list of the exempted documents can be found here and here.

The Freedom of Information Act also establishes an Information Publication Scheme (IPS). The scheme, which came into effect in 2011, says agencies must publish certain information on their websites. The material includes administrative elements (who we are, what we do), as well policies, plans and submissions to parliament. The Australian government’s Intellectual Property website is a prime example of the IPS rollout.

What to do if your application is rejected?

There are various avenues of appeal. The most common is to request a review of the decision by the Information Commissioner.

Following internal review, which includes submissions from the various parties, the Information Commissioner will uphold, overrule, strike out or modify the original decision.

Another option is appealing informally by contacting the organisation or agency that first rejected the application. This method of appeal is far less formal and more approachable for the general public. Resolution at this level would see both parties amicably solve the disagreement.

The third option for grieved applicants is the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT). Established in 1975, the AAT provides a cost-effective, informal means of challenging an administrative decision.

After lodging the claim with the tribunal, the process begins with a meeting between the applicant, a representative of the organisation or agency and a member of the AAT. If the situation cannot be resolved, subsequent meetings or mediation sessions may be scheduled. Failing that, a hearing takes place where a final decision will be made. A summary and explanation of the tribunal process can be found here.

Adria De Fazio is a second year Bachelor of Journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on twitter @adriadf.